When Marco Polo wrote about Kublai Khan in his book, he described a semi-legendary ruler, magnificent, and rich beyond imagination. Few believed him then. Europe knew little of Orient then, and even less about Kublai. The grandson of Genghis Khan, he ruled over the largest contiguous land empire that has ever existed. Like his grandfather, he showed talent for conquest, but unlike him, Kublai was an excellent administrator and very un-Mongol, if the situation demanded it. His reign was heralded as the Pax Mongolica, and his death marked the beginning of the decline of the Mongol Empire. Check his amazing story below:

1# The grandson of Genghis Khan

Kublai was born in 1215, the second son of Tolui and Sorghaghtani Beki. Tolui being the youngest of Genghis Khan’s sons, while Sorghaghtani was the niece of Toghrul Khan, former leader of the Keraites, a Turkic neighbour of the Mongols, and ultimately conquered by Genghis. Wielding the typical Mongolic tolerance for other religions, she had converted to Christianism, but her husband and offspring remained shamanists, worshipping the Sky God Tengri, like their forebears.

Little is known of Kublai’s childhood, except he was born and most likely raised in Mongolia, since he could only read and speak Mongolian. On Genghis’ death in 1227, Tolui wasn’t considered as a possible successor but acted as a regent until Ögedei, the third son of Genhis was elected as the new Great Khan.

2# Learning to rule

This wasn’t the end of the fortunes of Tolui’s line. Far from it. After completing the conquest of Northern China, Ögedei gave Sorghaghtani lands in the annexed territory, and she in turn gave Kublai a total of 10.000 households to administer on his own. In return, she gave her to support Ögedei’s son, Güyük, in the struggle for power after the former’s death. But Sorghaghtani was a woman of ambition, and when the chance came for her son, Möngke, to bid for the throne, she didn’t hesitate. He was elected Great Khan in 1251.

Meanwhile, Kublai learnt the hard way not to leave his affairs unattended. But learnt he did. Ever since, he’d always surrounde himself with Chinese advisors from the three main religions Confuciaism, Taoism, and Buddhism, to advise him in matters of governing. For military matters, the Mongols were the people to speak with. While Turks and Arabs were his choice for secretaries and translators.

Given more responsibilities by his eldest brother, his methods and results justified his growing reputation as administrator without par. Unlike the majority of Mongols, who being nomadic in nature, took little interest in agriculture, Kublai understood this to be the main source of taxation and income, and consequently nurtured it to the best of his ability. This would later explain his success in administering the whole of China without speaking a word of the language.

3# Brother against brother

The following decade was a busy one for Tolui’s sons, as they attempted to take on the Song of Southern China. Kublai was given a military command for the first time, and with the experienced general Uriyang-kadai as his second, was sent to conquer the kingdoms of Dali and Yuann, from where strikes at the vulnerable south-west flank of Southern China could be launched.

That’s why in 1258 he was given command of one of the three columns massed to attack Wuhan, on the banks of the Yangtze. But then news of Möngke’s death reached him. Mongol protocol demanded that all military operations cease until a new Khan was elected, but Kublai kept the news from his army to complete the capture of Wuhan.

Wuhan proved a tough nut to crack, and coupled with news of the deteriorating situation at home, forced Kublai to pull back. His younger brother and regent, Ariq Böke, had summoned a Kurultai (an assembly of the Mongol leaders) in his absence, and had been elected Great Khan. Kublai and other members of the family, objected, and while the Mongol traditionalists supported Ariq Böke, those with lands and interests in China, favoured Kublai.

4# The Toluid Civil war

Kublai held his own Kurultai, which on 15th April 1260, elected him Great Khan. Conscious of how his power base depended on the Chinese support, he capitalised on that, giving his reign the name of Zhong Tong, ‘moderate rule’ and chose Yuan ‘sublime’, as the name for his dynasty. Esentially, Kublai not only assumed the mantle of Great Khan, he also did the mantle of Chinese Emperor. It begun to dawn what his goal would be: the complete conquest and unification of China under his mandate.

But first, Ariq Böke had to be dealt with. Although Ariq was based in Karakorum, the Mongol capital, Kublai had the advantage of the vast Chinese resources and control of the trade routes heading to and from Karakorum. Several battles followed a blockade on Karakorum, after which Ariq was forced to flee into Central Asia. It was 1264 when he finally bent the knee, and although spared by his brother, he died two years later. Rumours that he had been poisoned have naturally persist, but are of course, impossible to prove.

5# Kublai’s capitals

One of the most important decisions taken by Kublai on the aftermath of the civil war, was that of moving his capital. He had not so long ago founded Shangdu, or Xanadu (Inner Mongolia, present-day China), but now he packed up and relocated to Zhongdu, better known as Khanbaliq or Daidu. The Forbidden city, the heart of Beijing, would be later built on top of Khanbaliq. Hence, Beijing owes it status as capital of China, to the Mongol Khan.

His foreign policy was also to have a lasting effect on modern Chinese nationalism. The annexation of Tibet by the People’s Republic of China was justified on the grounds that it always been a part of China. At least, after Kublai, that is. It was he who first set up a Bureau of Buddhist and Tibetan Affairs to rule the country, with his preceptor, the Tibetan monk Drogön Chogyal Phagpa, in charge.

6# The key to China

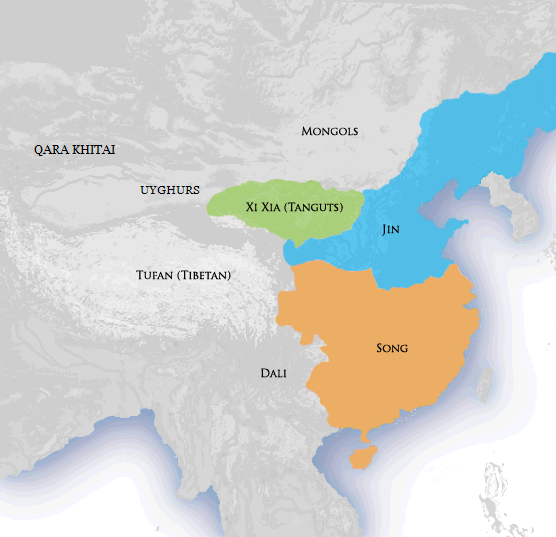

Having secured his position home, it was time to complete what his predecessors had failed to accomplish: the conquest and unification of all China. The Mongols so far, had only managed to conquer the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty of Northern China. The area was, and still is, different from the south-east of China, with vast steppes that favoured the Mongol horse-based tactics.

To conquest the remainder held by the Song, Kublai required of a different approach. He needed Han (Chinese) for his army, which he had plenty since the Jin lands had been subjugated in 1234. He also required boats, since the key to conquer Song, was the Yangtze River. To approach the Yangtze from the north, he’d have to use the Han River. And to use the Han River, he needed to take the city of Xiangyang.

7# The siege of Xiangyang

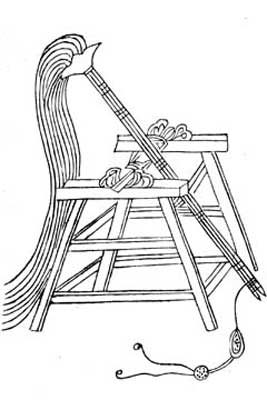

The city, straddling the banks of the Han River, did a great job in resisting the Mongol advance under Aju, the son of Uriyang-Kadai (who had conquered Yunnan fifteen years before). A protracted siege begun in 1268. Sorties, counter-sorties, and the exchange of trebuchet rocks and explosive posion projectiles known as Thunder crash bombs, were exchanged, but no side managed to gain the upper hand.

To break the stalemate, Kublai asked his nephew, Abaqa, the Khan of the Ilkhanate to send two engineers who knew how to construct and operate the newst version of the trebuchet. This deadlier variant had been known in the Muslim lands for some time, and would be called ‘Muslim catapults’, by the Chinese. Unlike the more widespread traction trebuchet, the new counter-weight trebuchets built by Ismail and Ala ad-Din, could and did smash the walls of Xiangyang to rubble. The city finally capitulated on March 17th 1273.

Marco Polo, who would hear the tale of the Siege of Xianyang, didn’t hesitate to claim authorship for the discovery of the new weapon. A blatant lie, probably penned by his co-author, the embellisher Rustichello, since Marco Polo wouldn’t arrive to Xanadu and meet Kublai until 1275.

8# The fall of Song

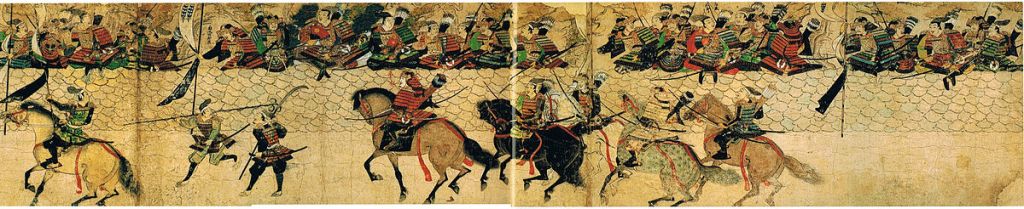

By 1275, the Mongol army had sailed down the Han and into the Yangtze, under the leadership of Bayan of the Baarin, with Aju as second-in-command. The military situation wasn’t hopeless, the Song had pplenty of men and resources, but unlike the Mongols, they were lacking in leadership. The emperor was three years old, and the unpopular Chancellor, Jia Sidao, having retreated in battle against Bayan, had lost all credibility.

Their fate rested on the shoulders of the Dowager Empress Xie. Perhaps wishing to spare the capital Lin’an, the fate of Changzhou, whose inhabtiants had been massacred by Bayan for resisting, on January 26th 1276 she sent a note to Bayan acknowledging Kublai’s overlordship. A month later, the young emperor Zhao Xian and his family begun the long march to exile in Beijing. He was allowed to relocate to Tibet, where he commited suicide in 1323.

But not all the Song were ready to submit yet. The loyalists enthroned two young princes, Zhao Xia and Zhao Bing, brothers of the deposed emperor and sent them to the far south, to rally the Han against the invader. They were finally and ultimately crushed by the Yuan navy at the battle of Yamen, in 1279. The Song dynasty thus officially ended.

9# The Emperor of China

For the first time in history, a non-Han dynasty ruled all of China, and more. The Han of course, never fully endorsed a regime in which they sat at the bottom of the social ladder, behind Tatars, Koreans, Turks, Arabs and Persians, and the Mongols on the very top. Although the Han remained essential to staff the civil administration and therefore never lacked employment. Many others, known as rejectionists, withdrew from public life in protest, while the more obstinate, or loyal depending on whom you ask, commited suicide before serving the Mongol lords.

But the discriminatory Yuan was also far more lenient that the Song had been. They halved the list of offences punishable by death, and arts, specially theatre, experienced a golden age. The new regime ushered an unprecedented period of internal stability, known as Pax Mongolica after the Pax Romana under Augustus, and booming trade with the Muslim lands. A province administrative system was created, which continues to the day, and the use of paper money backed by reserves of silk and silver was extended and reinforced. Quite telling is the fact that after Yuan fell in 1368, paper money fell out of use for nearly 400 years.

10# Late years. The invasion of Japan

Kublai did the impossible, but his ambition wasn’t satiated by the Song conquest. He believed, like his grandfather had believed, that the fate of the Great Khan was to rule all over the peoples and nations of the world. And if he didn’t, wasn’t for lack of trying. He had his way in Korea, where he installed Wonjong of Goryeo as his puppet king, but his attempts to invade Burma, Vietnam, and Java met with failure, while the losses derived of his two attempts to invade Japan were dismal.

Perhaps, his good judgement of old had been impaired by age, and by the death of his favourite wife and life-long companion, Chabi, and his son and heir, Jingim. Or perhaps like Napoleon, he thought the rest of the world would do his bidding, or be prod to with the sword.

10# Death and legacy

Kublai Khan died on February 18th 1294. Although the other three khanates acknowledged his grandson and heir, Temür, as the Great Khan, truth was, they were de facto independent. Not even a hundred years after his demise, while the Mongols lost their grip all over Asia, the Great Yuan was toppled by the Ming dynasty. Pushed back to the Mongolian steppe, the weakened Yuan managed to survive there as a rump state until the 17th century.

Ironically, it was in the West where Kublai’s memory fared better, thanks to Marco Polo’s The Travels. Marco’s description of his legendary riches, would serve as an inspiration for Columbus to set of on his famous trip to find a western sea route to China and the East Indies. A voyage which accidentally culminated in his setting foot on the American continent in 1492, paving the way for its subsequent colonisation by Europeans.

Hadn’t Kublai existed; the world might look very different from what it is today. Certainly, China would be much weaker and without Beijing as its capital. By conquering the Song and unifying the Han, Kublai had unwittingly strenghtened a formidable enemy for his Mongol succesors. His conquests of traditionally non-Han lands such as Yunnan, Tibet, western China, and the Manchurian basin, served as a justification for posterior Chinese dynasties to annex them as well, under the justification that they were the legitimate successors of the Mongol emperor.

It wouldn’t be too far-fetched then, to consider this Mongol-born conqueror who didn’t speak or write Chinese, the father of modern China?