Marco Polo’s name stands synonym for many things. Traveller, explorer, chronicler, writer, merchant, colorful storyteller, and pathological embellisher. Marco Polo became famous for co-authoring Book of the Marvels of the World, which narrates his nigh 25 year-long trip throughout Asia, in the process, meeting the fabled Kublai Khan, Emperor of the Mongols and grandson of Genghis Khan.

What he described was so incredible and detailed that his contemporaries easily dismissed him as a fraud. In an age where the average person seldom travelled further than the boundaries of his native village, the marvellous sights and imperial grandeur described struck the medieval audiences as pure fantasy. Even today, it’s too easy to be sceptical in regards to his book. Why? Keep reading.

“I did not write half of what I saw, for I knew I would not be believed“

Marco Polo

1# The Venetian

Marco Polo was born in the Republic of Venice in 1254. His family belonged to its nobility, which made its fortunes in trade. His father, Niccolò Polo, together with his uncle, Maffeo, had departed on a long trip before Marco was born, leaving him to be raised by his mother. They had journeyed to the confines of Asia, to China, where they had met the Mongol emperor Kublai Khan himself. In fact, Marco didn’t meet his father until he turned sixteen, when the Polo brothers finally returned to Venice.

2# The East

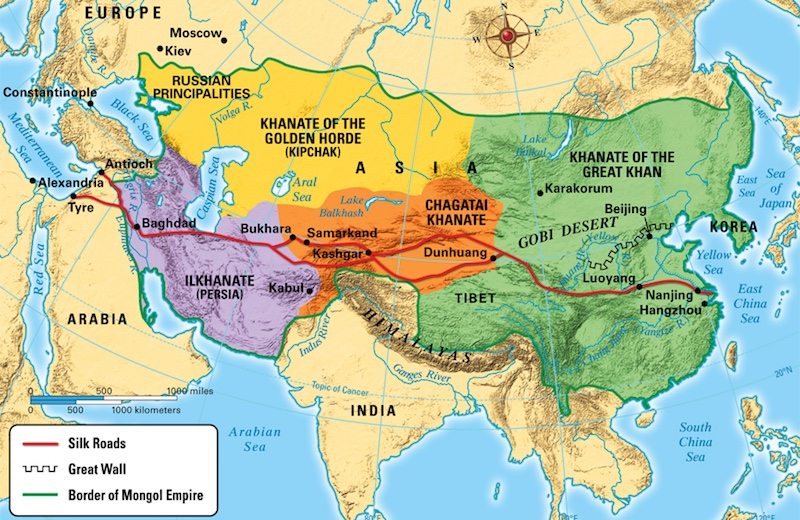

The conquerors and masters of nearly all of Eurasia, thanks to their unparalleled horsemanship and adaptability, the Mongols have been easily dismissed as mindless barbarians and destroyers for too long. Although certainly fearsome, the Mongol horde and its enlightened leader, Kublai Khan, weren’t all riding, killing, and looting. They also sought to promote trade, and were particularly accommodating of other religions and customs.

Albeit already familiar with Christianism, the appearance of two rare Europeans in his court was too rare an event for the Khan to pass. He entrusted the Polo brothers with a three-fold mission: to deliver his letter to the Pope, to promptly return with a hundred wise, Christian, men to proselytise amongst his people; and to bring some of the oil of the lamp that burnt in the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem.

However, when the brothers returned to Venice in 1269, they learnt that the Pope had died a year earlier, and no replacement had been elected yet. Hence, they had no choice but to wait.

3# The Holy Land

Like father like son, the teenager Marco joined the elder Polos as they readied for their second journey. After all, trading was the Venetian’s hallmark, and how best to learn the profession than by witnessing it firsthand? Two years had passed waiting for a new Pope in vain, and not wishing to upset Kublai Khan for further postponing their return, the three Polos set off to Acre in 1271.

Acre served as the capital of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem, ever since the holy city had been conquered by Saladin in 1187. Christiam pilgrims were still granted safeconduct to visit it, and the Polos promtly headed there, were they obtained some of the oil from the lamp in the Holy Sepulchre. Afterwards, they returned to Acre to confer with the local Papal legate, Teobaldo of Piacenza.

Despairing of hearing of the election of a new Pope anytime soon, the Polos departed to Ayas (modern Turkey) to begin the journey, only to receive word that a new Pope had been elected at last, and it was no other than Teobaldo himself. Teobaldo promtply recalled them, and gave them money and gifts for Kublai Khan, as well as two friars who were the act as his envoys to Kublai Khan. Fortified with the Papal authority and blessings, the Polos departed east.

4# The Ilkhanate

As it turned out, Papal influence extended only so far, and at the first sing of trouble in the unstable Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, the two friars turned tail. Not the Polos. They weren’t motivated by ambition like the Pope, or fervor like the Crusaders. As merchants, their God was money, and they sincerely held fast to the belief that great profits could be reaped in the East.

As fraught with conflict as it has always been, and still is, the Polos were surely glad to see the last of Levant. They entered into the Ilkhanate, the westernmost Khanate of the Mongol Empire, and visited some of its wealthiest cities like Mosul, Baghdad, and Tabriz. Although the Mongol conquest had brought their Golden Age to an abrupt end, these cities were still wealthy for Western standards.

They were in Persia (modern-day Iran), and in the eyes of the young and impressionable Marco, it must have been as though he was following the steps of his heroe, Alexander the Great. The original plan was to reach Hormuz, and then take a boat to take them to China by sea, but having seen the poor craftmanship of the local ships, the boat-builder that inhabited every 13th century Venetian decided to walk to China. They must have been appalled at what they saw, for a traveller on foot faced as many dangers as a sailor, without the benefit of a shorter journey.

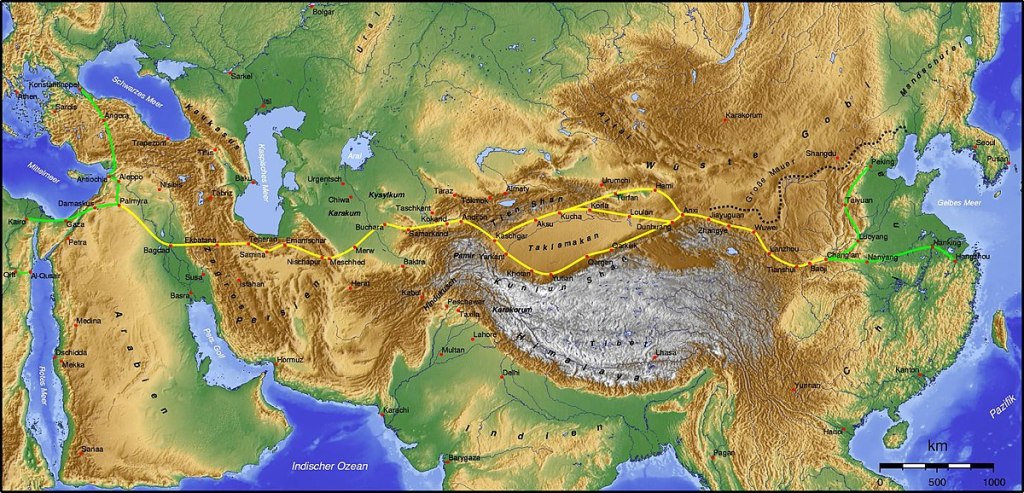

5# The Silk Road

They purchased Bactrian camels, the favourite choice of transportation for arduous crossings of arid landscapes like those of Afghanistan, where Marco, always with a merchant’s eye, described the local produce: salt, almonds, and pistachios. Nor he could have failed to notice the poppy opium, as Afghanistan was and remains the world’s leading opium producer. Marco fell seriously ill there, perhaps with tuberculosis, which has led to the speculation that he used opium to treat the disease, a common remedy of old for tuberculosis.

Whatever it was, it was doubtless serious, for they lingered for one year, waiting for him to recover. The increasingly thinning air must have helped though. The Polos kept steadily climbing up, and across the mountain range of Central Asia, where the world’s tallest mountain ranges, including the Himalayas, Hindu Kush, Karakorum, and Tian Shan, intersect. The Polos favoured entering China through the Terek Pass (Kyrgyzstan), which cuts across the Pamir Mountains.

With the altitude never dropping below 3500m, hardships included scant oxygen, bitting cold, lack of food, and treacherous footing. However tough, the trekking didn’t dull Marco’s powers of observation, as he commented, amongst other things, about the local breed of sheep. Nowadays, his bleating, woolly acquaintances honourably bear the name of Marco Polo sheep.

Kelvin Case. Source

6# The desert crossing

When they came down at last they briefly paused at Khotan, where Marco had a first taste of Buddhism. It failed to impress him, but he was still very young, and his travels had still to soften up his callous Christian conceptions and inflexible thinking.

Khotan was nonetheless a welcoming sight. It is an oasis at the edge of Taklimakan Desert, in western China. Not only is Taklimakan further from any ocean than elsewhere in the world, its name is said to mean “Desert of the Death” or “Place of no return”. Not quide the idyllic ambling after the wheezing trek near the roof of the world. And if one desert wasn’t enough, two more followed the first. The Lop and Gobi deserts.

7# Kublai Khan and the Great Yuan

It was the year 1274, and the Polos had spent three years travelling the Silk Road. No wonder Marco’s claims strained the credulity of those who bothered to pick his book. A year later, he got to see Xanadu, also known as Shangdu, the summer capital of Kublai Khan. The larger and most prosperous of the four khanates that formed the Mongol Empire, the Yuan―which encompassed all of China, Mongolia, parts of southern Russia, and chunks of South-East Asia―was the personal fief of Kublai Khan, who was also the Great Khan of the Mongol Empire, and therefore nominal overlord of the other three khanates.

Marco was duly introduced to Kublai, and their gift of the lamp oil of the Holy Sepulchre was received with great pleasure. Marco proceeded to describe him as the greatest, most magnanimous, and most generous ruler that had ever existed. Even as great as his hero, Alexander! In an age where the West knew practically nothing of the Mongols, and regarded them as God’s scourge, Marco’s praise of their leader must have seen as the product of the devil himself.

But if one accounts for the following 17 years that Marco spent working as an envoy and tax collector for him, travelling across all the vast Yuan, it’s no surprise at all. Although Marco doubtless exaggerated whenever he spoke of his importance to Kublai Khan, there is no reason to doubt that the emperor had him in high esteem. But he wasn’t the first foreigner whom Kublai Khan elevated in order to further his own goals. He just happened to be a rare European, and Christian at that, just like his mother, Sorghaghtani.

8# Emissary of the Khan

Thanks to the possession of a Paiza, the equivalent of a Mongol passport that afforded diplomatic immunity to the bearer, and to their efficient post system; Marco could travel safely across the Grand Canal from Daidu, also known as Khanbalikh (modern-day Beijing), Kublai’s new capital, to Hangzhou, then the capital of the former, native-Chinese, Song dynasty, which was only fully conquered by Kublai’s troops in 1279.

Across the Yuan, Marco came across many experiences vaguely known by Middle-Age Europeans, such as Silk manufacturing and noodles, or pasta. Contrary to popular belief, he didn’t introduce pasta to Europe. It was probably done so by the Emirate of Sicily, in the 9th century. He also wrote about paper money, eyeglasses (in the form of lenses), coal, firecrackers, and gunpoweder, all virtually unknown to Europe but common knowldge amongst the Chinese. All these findings would revolutionise our economies and armies, and would turn the western European countries into the dominant powers of the following centuries.

He went further beyond the borders of the defunct Song dynasty, to Burma, Tibet, and Vietnam, the latter a vassal state of the Great Yuan. Although he didn’t visit Japan or Java, he described the disastrous outcome of Kublai’s attempts to subjugate both. He also talked at length about Buddhism, no longer as a suspicious and zealous Christian, but as an impartial (or nearly so) traveller.

9# The Mongol Princess

If reaching China had been hazarduous and even life-threatening, getting out wasn’t to be any easier. Kublai Khan, growing distrusting and resentful in old age as a result of his fiascos in Japan and Java, and the abuses of some of his officials, intepreted the potential departure of his valuable European subjects as an invitation to future challenges to his authority. Marco explains how he, Niccolò, and Maffeo, were growing fearful of the sudden death of the Khan. For should it happen while they were trapped there, Kublai’s dormant enemies would be emboldened to settle some old scores with his favourite foreigners.

In the end, a solution that allowed both parties to save face, was found. Kököchin, a Mongol princess, was waiting to be sent to the Ilkhanate to marry Arghun Khan, the local ruler and relative of Kublai. The latter agreed to allow the Polos to escort the princess , even when he must have known in his heart, they wouldn’t return to him. He gave them 14 ships laden with treasure and warmly bid them off. It was 1292, and it was the last time that Marco saw the Great Khan, to whom he had faithfully dedicated 17 years of his life.

10# The lost ships

On the journey back home, Marco also sailed to Indonesia, India, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), and the island of Zanzibar. He circumnavigated the Indian subcontinent and made landfall in Hormuz. From there, many years ago, the Polos had declined travelling to Yuan by boat. They could only have bitterly lamented not sticking to their original decision this time. 14 ships had departed but only one had arrived. There were only 18 survivors, including the three Polos and princess Kököchin. The fate of the other thirteen ships remains a mystery. Either Marco Polo never explained it or his explanation has been lost, although it’s likely they fell prey to a combination of piracy, disease, and storms.

Arghun Khan had passed away before they arrived, but it was agreed that Kököchin would marry his son, Ghazan. Although reluctant to part from her companions, she finally set them free after they had spent nine months stuck in her new court. The Polos travelled to Trebizond and then Constantinople in 1295, where they boarded a ship bound to Venice. Marco was home at last, after 24 long years.

11# The Travels

During their return they learnt of the passing of Kublai Khan, at the respectable age of 78. With it came the end of the Pax Mongolica, which had allowed travellers and merchants like the Polos to travel the Silk Road in unprecedented safety. Centuries would pass before East and West would be so closely connected, and it would be through sea then.

But although Marco never set foot outside Italy again, there were still adventures left to him. Venice was at war with Genoa, its maritime rival. Like all affluent citizens, Marco paid for a ship and its crew to fight the enemies of the republic, but he was captured in action and imprisoned in Genoa.

As befitting a noble, he was kept locked in certain comfort, and there and then he met Rustichello de Pisa, a fellow inmate and romance writer. Together, they composed the Book of the Marvels of the World, better known to us as The Travels of Marco Polo, and by Marco’s contemporaries as Il Milione.

12# Last years

Marco was released in 1299, after Venice and Genoa concluded peace. He married Donata Badoer, of a noble Venetian family, and they had three daughters, Fantina, Bellela, and Moreta. The Polos became well-off thanks to the wealth they had amassed while in China, and Marco continued the family business with his father and uncle, and then with his sons-in-law after the former passed away.

He became a penny-pincher in old age, even petty, and truculent, prone to take others to court, even family, over unpaid debts. It’s hard to blame him when most people around him challenged his claims, and some even openly called him a liar. He had brought a Mongol servant with him, whom he called Peter, and whom he released on his deathbed, granting him a generous sum of money. This was on January 8th 1324. After a long convalescence in bed, Marco Polo expired after dictating his last will and receiving the last rites. The original document is still preserved in Venice.

13# Legacy and influence

It would take centuries for Marco Polo’s claims to be finally considered bona fide, if not always accurate and certainly, not properly translated. The original copy, written in vernacular French, and not even a good one at that, has been translated and re-translated so often, that many inconsistencies or discrepancies mustn’t necessarily be regarded as malicious fabrications of its authors.

It has been proven since that many of the events described in detail by Marco, in particular his return journey with the princess Kököchin, were likewise recorded in China. His book also influenced the Catalan Atlas and Fra Mauro’s Map, both regarded as the peak of medieval cartography. The mighty Yuan barely outlived Marco Polo himself, collapsing in 1368, and little survives from Kublai’s fabled capitals, Dadu and Xanadu. But they all still magically come to life again and again, through Marco’s words.

Cristopher Columbus, the first European to set foot on America since Leif Eriksson in the 11th century, carried a copy of the Travels of Marco Polo, and stumbled into the continent by pure accident. He was in fact, trying to find a faster sea route to China and India. He was Genoese by birth, the archenemy of Venice. Perhaps Marco Polo would have found this amusing. Or perhaps not. He had after all, nearly visited the whole known world.