In the 5th century, the days of glory of the Roman Empire were a warm but distant memory. The bright sun of Augustus and Trajan had set forever, and its many enemies could already smell its blood. Chief amongst them stood Attila, king of the Huns. Who was he? Where did he and the Huns come from, and why is he remembered and reviled, while other barbarian kings and their roles in the fall of Rome, have faded into history? Let’s explore it together:

1# The origins of the Huns

Even as today, nobody is quite certain where the Huns ancestral lands were, or even what their ethnicity, or language were. Even during Attila’s lifetime, no historian or writer posed the question, perhaps because to do so was to acknowledge their utter ignorance on the topic. The mystery reimained until the 18th century, when French scholar Joseph de Guignes, proposed a theory that linked the Huns with the Xiongnu.

The Xiongnu were a nomadic tribe, most likely of Turkish stock, who emerged from northern China (today’s Chinese province of Inner Mongolia) and around the 3rd century BC they spilled into Mongolia proper, to establish their own nomadic empire. This was long before the appearance of the Mongols and Gengis Khan, to whom they bear no connection other than they settled the same lands in different time periods.

It was on their account that the first emperor of the Qin Dynasty built one of the earliest sections of the Great Wall of China. The Quin succesors, the Han, waged war against the Xiongnu for most of the latter’s existence. Worn out by the drawn-out conflict, the Xiongnu were finally crushed and scattered by an alliance of clans from Manchuria in 89 AD. Its possible then, that the remains of the Xiongnu migrated west then, and came to be known as the Huns?

2# The decline of the Roman Empire

When the Xiongnu apparently vanished into the vast emptiness of the Asian steppes, Rome was reaching the height of its power. By the mid 4th century however, the empire was eroding fast, having to contend with nearly constant intericine struggles for power, a decline in population, corruption, increasing difficulties in managing its multiethnic provinces, and the religious strife brought about by the adoption of Christianity by Constantine the Great.

Moreover, since the death of emperor Theodosius I in 395 AD, the Roman Empire had been permanently split in two. Pressure, also came from the outside its borders. Goths, Visigoths, Ostrogoths, Franks, and Vandals, all pushed west by the migrating Huns, trudged into the Roman borders. With its weakened legions lacking the necessary manpower to stop them, Rome had no choice but to take them in, the loyalty of these barbarians was often to their own chieftains, and only pledged alliance to Rome when it suited their interests, or their pockets. The culmination of this inefficient immigration policy was the sack of Rome by the Visigoths of Alaric in 410 AD. Worse was to come.

3# The mounted warriors of the steppes

But what made the Huns different from the other barbarians harassing the empire? The Huns were a nomadic, pastoral tribe. Although their herds provided them with the basic necessities, they yearned after the luxuries that only complex, urban centres such as those found within settled societies like those of an empire could provide.

To make the Roman purses lighter, they had two weapons in their favour. Their composite bows made of wood, tendon, and horn, which allowed them to outclass those of other nations. And their mounted skills, which allowed them to shoot on horseback, thus striking fast, feigning a retreat only to strike again, without giving a chance to the enemy to counterattack. There was yet another decisive factor that made possible their sudden and explosive conquest: leadership.

4# The rise of the Huns

The Huns made their first recorded appearance in 384AD, as mercenaries in the service of the legions. It was more than likely than by that time they had already begun to settle in the Hungarian plains. Under the leadership of two chieftains, Basich and Kursich, they pillaged Roman Thrace, and after galloping all the way around the Black Sea and crossing the Caucasus Mountains, they invaded Armenia, Persia, and the Roman provinces in the Levant. It was the Persians, not the Romans, who finally beat them, although many Huns managed to escape and return to their new home laden with plunder.

Under a new leader, Uldin, nine years of peace ensued, only to be broken when he resumed incursions across the Danube, to strike at the Balkans once more. Undermined by his generals and soldiers in 408, when many of them defected to the Romans under the promise of gold, Uldin fled back home. There he died sometime before 412, when a new king of the Huns was mentioned, Charaton.

The next known kings were Ruga and Octar, who succeded in browbeating Constantinople to yield more tribute to them. When Octar died fighting the Burgundians, Ruga became the sole ruler of the Huns. Attila and Bleda, his newphews succeded him shortly after he died, possibly around 435.

5# Attila, King of the Huns

The brothers lost no time in tightening the noose around the neck of the Roman emperor in the East, Theodosius II, demanding further tribute and the return of Hunnic refuges who had fled from their authorithy. Their policy differed in the west, where they were, for the time being, content to work with Aetius. Aetius, an old friend of their uncle who had helped him secure the position of Magister Militum, commander-in-chief of the Western Roman Empire, then under the rule of Valentinian III. Together with Aetius, they descended on the Burgundians and obtained revenge for Octar’s death. Their slaughter became the inspiration for the epic poem of The Song of the Nibelungs.

No later than 447, Bleda disappearead from the scene, and its possible that Attila had him removed by force. Attila, whose only description came from the Roman sources, and the Romans felt nothing but disdain tomards the Huns. They were invariably described as small, bandy-legged, and brutish, just as the Mongols would be pictured by their many defeated foes. Attila himself, was also said to be mercurial in his moodiness, skillfull in flaring his temper when intimidation could yield profit, suspicious, and often brutal.

Faced with a lack of a Hunnic point of view, it’s impossible to say whether the real Attila matched this most unfavourable description. His actions, however, tell us something for certain: he had the necessary ambition to surpass his predecessors. He was no longer content with tribute for his people. He was seeking to encroach and expand into the empire itself.

6# Constantinople

Learning of the collapse of a portion of the walls of Constantinople by 447 as a result of an earthquake, he rushed south with his horde to seize the opportunity, only to find the walls rebuilt and strengthened in record time thanks to the efforts of the prefect Cyrus. He didn’t leave empty-handed though, returning home with the Roman promise of an annual tribute of 2,100 pounds of gold. Roman sources enjoy saying he was bleeding Constantinople dry but this seems to be an exaggeration, for the annual revenues of the Eastern Roman Empire amounted to 270,000 pounds of gold.

In addition to, Attila forced emperor Theodosius II to return the Hunnic refuges and to cede larges swathes of the southern Danube to him, thus depriving the Romans of critical forts and bases for their fleet there. Later, he would give the new lands back in return for further ammounts of cash.

7# The Invasion of Gaul

Although the West didn’t have to contend with Attila so far, thanks to the good relationship between him and Aetius, they were too tempting a target to ignore for too long. Honoria, the older sister of Valentian III, was rumoured to have given him the perfect excuse to extend his pillaging there.

She had been caught having an affair with her chamberlain, Eugenius, who was consequently put to death by her brother. Honoria seeking to revenge herself, and some say to satisfy her ambition of ruling, sent a message to Attila in which she offered to become his wife. Attila couldn’t have failed to see the implications of this. Honoria’s dowry would be the empire itself. He pressed his claim, disregarding the fact that Honoria had been already married off, against her will, to a Senator, some nonentity who had no designs on the throne.

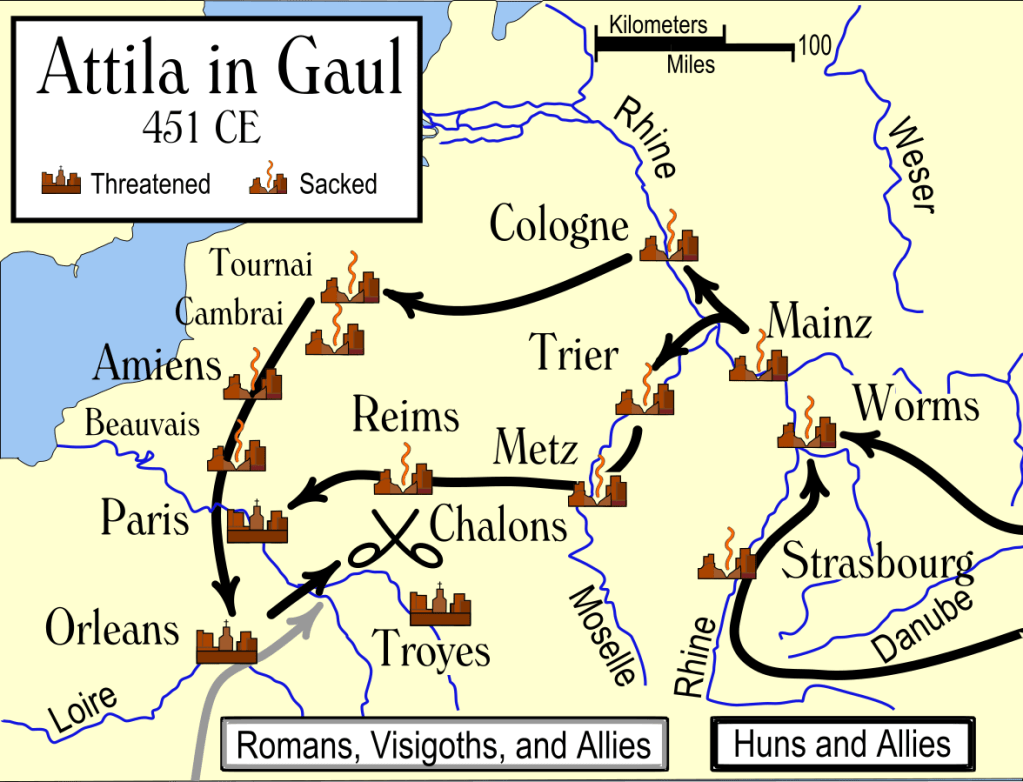

Whether he needed a dubious pretext to invade the western Roman empire or not, in 451 Attila crossed the Rhine River near Koblenz, and entered Roman Gaul. He divided his forces in two. One marched north to subdue the Rhineland Franks, who had settled around Cologne, while he himself marched towards Aurelianorum (Orléans). Apart from the Huns, his army counted amongst his ranks with Alan, Rugii, Thuringi and many other tribes subjugated by the Huns.

Attila and his multi-ethnic army bypassed Trier, but sacked Metz, before riding into the open expanses of Champagne, an area then known as the Catalaunian Fields. On reaching Troyes, its bishop, Lupus, surrendered the city in order to spare its citizens. From Attila’s lips, the Chrsitan chroniclers attribute the famous statement spoken to Lupus: ‘Ego sum Attila, flagellum Dei’. I am Attila, the Scourge of God. For the Christians, it was easier to believe that Attila was thrashing them because he was the instrument of God’s wrath.

8# The Battle of the Catalaunian Plains.

With God or not on his side, Attila had enemies to contend with: Aetius, his former ally and commander-in-chief in the west, and the Visigoths settled in southwest Gaul, whom Aetius had brought into a temporary alliance to fend off the Huns. The Roman-Gothic army won the race against the Huns towards Aurelianorum, thus preventing Attila to take it. Another version declares that the Huns were already besieging the town when Aetius and Thedoric, the Visigoth King, forced them to desist. Attila marched back the way he had come, but on the Catalaunian Plains (possibly near Châlons-en-Champagne) he turned his army to give battle. It was June 20th 451AD.

No reliable estimates of the armies’ sizes exist, but combined they might have numbered around 100.000, possibly much less. The battle resulted in a stalemate but while the Romans and Visigoths had the advantage of shorter supply lines and could replenish their losses, the Huns could not. The former might have pressed their victory and even perhaps capture Attila, if not for the death of Thedoric in battle. Aetius, wary that an uncontested victory might strengthen the Visigoths too much, sought to persuade Theodoric’s son, Thorismund, to relinquish a pursuit of the retreating enemy, and instead rush home to secure his father’s succession. Attila, defeated but not broken, retreated towards the Hungarian plains. The West hadn’t yet heard the last of him.

9# The Italian Campaign

Next year he launched another invasion, this time intending to take Rome and Ravenna, which had become the capital of the Western Empire since 402AD. He crossed the Julian Alps, the border between modern Italy and Slovenia, and razed Aquileia to the ground after a contested siege. He then followed the Po Valley west, instead of heading straight south for Ravenna, and then south-west to Rome.

Why? Perhaps he dreaded to suffer the same fate as the Visigoth king Alaric, who had sacked the Eternal City in 410, only to die shortly after. There was also his nemesis, Aetius, blocking his way to the passes towards Ravenna and shadowing his larger force. Moreover, his army was ridden with disease and low supplies, and he must have been worried by the incursions on his Hungarian lands by the new eastern Roman emperor, Marcian, who had ceased to pay him the tribute of his predecessor.

A Roman embasy headed by Pope Leo I, former prefect Trygetius, and the ex-consul Avienus, was sent to him to seek terms. After meeting them, Attila decided to return home. Christian chroniclers loved to call it a miracle and attribute it to the Pope’s intercession with God, but the truth was that, for the reasons mentioned above, Attila didn’t simply have the necessary means to take Ravenna and Rome, and much less keep them.

10# The death of Attila

The booty and tribute must have been exceedingly large, and the prospects of a future invasion and even more gold, promising enough. Attila was still at the summit of his power, his authortithy uncontested at home, feared by his enemies, and rich from his campaigns. The year was 453, and nobody had expected to find him dead on his bed after his wedding night with his last wife, Ildico.

Some would readily give her credit for murdering Attila as a revenge for her slaughtered kinsmen, but most historians agree that the real cause of his death was a hemorrhage, likely due to ruptured esophageal varices, which usually appear on people who consume large ammounts of alcohol. Knocked out with wine and lying on his back, the great warrior ingloriously choked on his own blood.

He was buried with great honours on the bed of a diverted river, which was brought back to course to conceal his final resting place. Inevitably, the myth that all those who knew of the location had been murdered to prevent its discovery, spread. A common but false occurrence that writers of old attributed to several other kings and rulers such as Alaric or Gengis Khan.

11# Legacy

His empire didn’t survive him for long. His sons, Ellac, Dengizich, and Ernak, bereft of instructions as to whom should succeed him, quarreled. The Gepids, one of the Huns’ vassals, rose in rebellion and defeated them in the Battle of Nedao, killing Ellac in the process. It was the beginning of the end. Under Dengizich, the Huns made one last desperate incursion over the Danube in 467. They failed, and Dengizich’s head ended up in Constantinople, where it was put on top of a stake in the Hippodrome. The remains of the Huns either merged with other tribes, or scattered back into the steppe that had had regurgitated them. They disappeared from history as abruptly as they had appeared.

For all the awe that his name inspired, Attila changed very little in the grand scheme of things. Even accounting for the Huns’ impact on the migrations of the late fourth and fifth centuries, the Western Roman Empire already faced a multitude of internal problems and fracture that probably would have led to its inevitable demise, regardless of the Huns. They probably only accelerated the process.

His legacy is that of the boogeyman of the Romans, an infamy cemented by years of raiding and plundering. He didn’t build, made and codify laws, didn’t promote or show interest in culture or arts, or strived in any other way towards a wise administration and the betterment of his people, other than through the extortion of tribute. He was simply a bully with the power of an empire on his hands, who offered nothing but destruction and who created nothing.

At least, as long as you don’t ask someone from Hungary. The Hungarians, or Magyars, who also came from the East, settled in their present location at the turn of the ninth century, under Árpád. Just like the Xiongnu or Huns and the Mongols, they have no connection with one another, but despite this, Attila is honoured as a predecessor of Árpád, the nation’s founding father, and his name is still valued and bestowed on Hungarian children. Revilded by many, worshipped by others, such is the fate of many famous leaders in history.