The D-Day landings, or Normandy landings, were the biggest amphibious operation ever, and it is considered a decisive victory for the Allies in WW2, against Nazi Germany. US, British and Canadian troops, among other nationalities, landed in five beaches: Utah, Omaha, Juno, Gold, and Sword. It was the beginning of the liberation of Nazi-occupied France. Read the second part here.

#1 D-Day landing beaches

By the fall of 1943, and despite his Red Army’s great victories of Stalingrad and Kursk, Stalin was nagging the Western allies (US, UK, and Canada) to open up a front in France, a thus relieve the suffering USSR territories under the Nazi yoke. Churchill and Roosevelt, promised him to do so by mid-1944.

Following months of preparations and planning, the SAHEF amassed over 150.000 soldiers and over 5.000 war ships for Operation Neptune, the first stage of Operation Overlord. Neptune’s goal was to secure footholds in Normandy, capture the strategic Carentan and Saint-Lô to isolate the Cotentin Peninsula (by US Army), and Caen (for the British and Canadians) to establish airfields. Five beaches were selected for the purpose. The codenames were: Utah, Omaha, Juno, Gold and Sword.

The stalemate of the Italian front and the bitter failure of the Dieppe Raid in 1942, prompted the Supreme Allied Headquarters Expeditionary Force (SAHEF), commanded by Eisenhower, to choose Normandy, since Pas-de-Calais was the most fortified, and the most obvious choice for Hitler. Deception was a key feature of the invasion. Operation Fortitude led the Germans to believe the attack was to take place near Pas-de-Calais, because of an intense, but fake, radio activity.

The Allies went as far as to create a fictional 1st US Army, under the controversial George S. Patton, lining up inflating tanks and ships, dummies, and empty tents. A true ghost army that kept the OKW (German High Command) deceived, even after the Normandy landings had taken place.

#2 The Atlantic Wall

Meanwhile Wehrmacht units enjoyed the mademoiselles of the French capital, trying to forget the horrors of the Eastern front, where the Red Army had pounded them hars. In charge of them was Field Marshall Karl Rudolf Gerd Von Rundstedt, and Hitler, appointed Field Marshall Erwin Rommel, the ‘Desert Fox’, one of Germany’s most brilliant generals, to supervise the defences of the Atlantic Wall.

Because Hitler had diverted concrete to build his massive U-Boat Atlantic bases, few was left to fortify the coast. On top of that, the Panzer reserves, the true Wehrmacht’s strength, were to be used only on Hitler’s authorization, and because of the Allies insulting air and naval superiority, they had to be kept hidden.

Defending the Utah and Omaha sector, was the German Seventh Army. The British-Canadian sector was defended by the Fifth Panzer Army (renamed Panzer Group West). Both under Rudnstedt’s overall command, they included over 850.000 fighting men. Many were captured Poles or Hiwis (USSR soldiers) who had been forcibly conscripted in the Wehrmacht. Others were ‘ear and stomach battalions’, having suffered stomach wounds or loss of hear. Unsurprisingly, they couldn’t care more when furious officers yelled at them.

Still playing to soldiers and generals, Hitler insisted in giving orders from his headquarters in East Prussia, (while also handling the Eastern Front himself). Essentially the German command was already enough over-complicated, orders being issued from the OKW (Hitler), from the OKB (Rundstedt), Army Group B (Rommel), the Seventh Army, and the Fifth Panzer Army.

However, Rommel was the cunning fox his nickname suggested, and went to great lenghts to reinforce the coastal fortifications. French tank turrets captured in 1940, known as Tobrouks were emplaced in the bunkers, and wide stretches of land were punctured with posts known as ‘Rommel asparagus’, to prevent American and British gliders to land enemy soldiers and supplies. On top of that, the Waffen-SS divisions hardened in the Eastern front, would prove more than a match for the Allies, thanks to their exceptional moral and training.

#3 D-Dayparatroopers

The date for Operation Neptune was the 1st May. The operation was delayed, and finally was decided to launch on June 5th. Again bad weather messed up Eisenhower’s expectations. But on the 6th, a tiny window of not-too-bad weather popped in, amidst warnings of rough sea and winds during the oncoming days.

On the evening of 5th June 1944, the Allied Army embarked in the south English coast, ready to invade the Nazi-infested continent. Over 130.000 soldiers packed in their mother ships, plus another 25.000 paratroopers distributed in 1.200 aircraft, ready to drop at the German’s back. The armada was escorted by six battleships, four monitors, twenty-three cruisers, 104 destroyers and 152 escort vessels, as well as 277 minesweepers who would clean ‘safe channels’ to access the beaches.

The fearsome devils of the 101st Airborne, and the 82nd, wore a Mohawk styled single fringe of hair on their skulls, to frighten the Landser (German veteran). Together with their British counterpart, the 6th Airborne, they flew over the Channel aboard the C-47s, several hours ahead of the armada.

Meanwhile, the French Resistance, waiting impatient in front of their radios, sprung to action when the speaker said the magic words: Les dés sont sur le tapis (The dice are down). With a ferocious lust for revenge, they began cutting cables, telegraph, and blow up railway. Their efforts were to prove critical at delaying the German response and reinforcements.

After midnight the C-47s reached the French coast, descending to 1.000 feet for the drop, but that left them within range of the Flak anti-aircraft. Slipping on the vomit soaked floor, and tossed around because of the dodgy-dizzy manoeuvres, the terrified soldiers struggled to dive out. Some needed an encouraging kick from their officer, and some got broken legs and ankles when their C-47s descended lower than 500 feet. Others suffered broken backs, or died, when their parachutes lacked time to open.

The Germans had flooded fields in anticipation of the airborne assault, and some paratroopers, excessively dragged with ammunition, food, tools, and a soaked chute, drowned. Others dangled and wriggled on the tree bowls, targeted and bayoneted to death by the Germans. However, the chaotic dispersion caused by the anti-aircraft fire played to the paratroopers advantage. The Germans thought the Yankees and the Brits were everywhere on the damn creation.

Abandoned gliders in a field in Normandy. Gliders could land troops, supplies and even jeeps. Author: Royal Air Force official photographer. Source

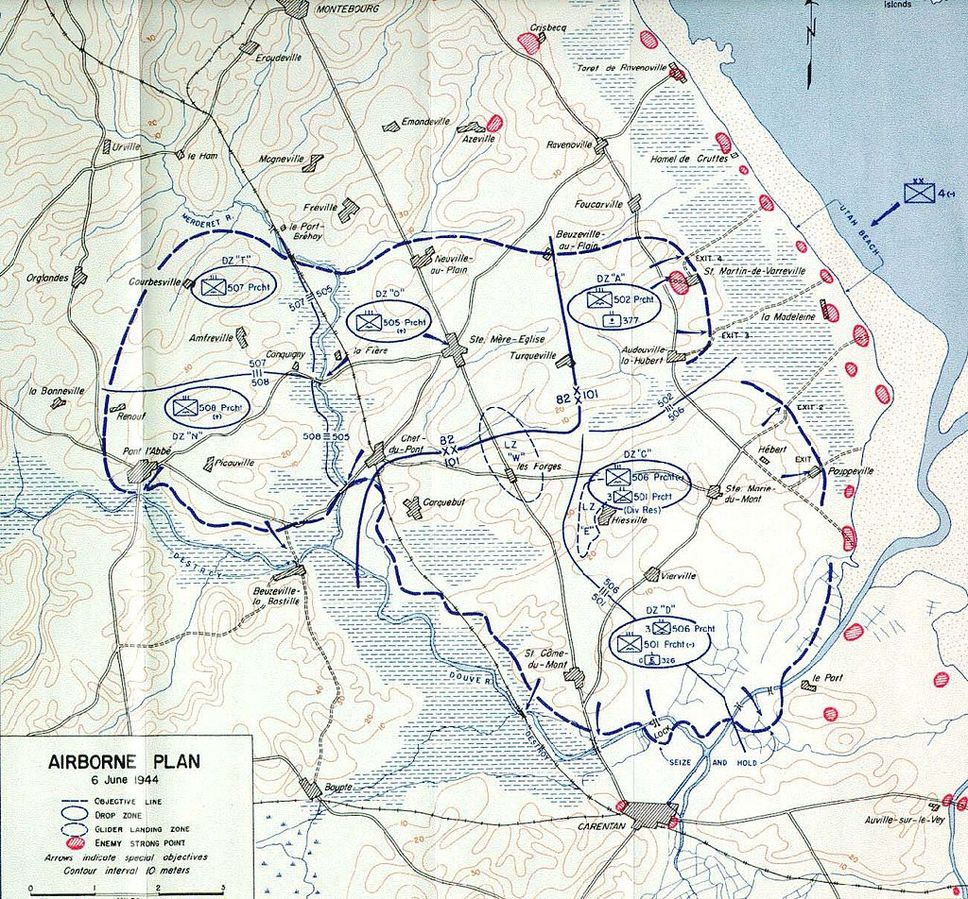

US paratroopers landing areas circled in blue. Utah beach is marked in blue too, up on the right. Author: Historical Division, Department of the US Army. Source

Armed with knives, sub-machine guns and grenades, they immediately began to dispatch the confounded defenders. To identify their colleagues in the darkness and chaos of the night, the paratroopers retorted to the password ‘Flash’, to which the correct reply was ‘Thunder’. These words were chosen because they were thought to be difficult to pronounce convincingly by German speakers.

The 6th Airborne captured the bridges over the Orne, and secure the left flank of the Sword beach, while the 101st and the 82nd were dropped on the base of Cotentin Peninsula, where they seized the roads and bridges leading towards Cherbourg, a vital port for the Allies to capture, and thus increase the volume of supplies.

#4 The longest day

Meanwhile, at 01.00am, the assault forces were given a hefty breakfast aboard the ships. They geared up, and wrapped their rifles in plastic bags and condoms, to seal them from sea water. At 5.20am, in squads of 36, descended into the Landing Crafts, bouncing in the rough sea beneath the steel battle ships. Ahead of them, the minesweepers had managed to clear channels, and surprisingly did it without casualties.

Special mention for the Kriegsmarine, under Großadmiral Karl Dönitz, who failed to send a single U-boat into the Channel. Above their heads USAAF and RAF bombers commanded the skies, and began dropping their deadly regards above the beaches, hoping to flatten the machine guns nests and strongholds. Shortly after the destroyers joined the fire storm, shooting above the landing craft, the water rippling due the powerful calibre of their guns.

The sea was wilder than expected, and as a result the American troops heading for Omaha and Utah were diverted from course, with a mix of positive and negative consequences. The British landings in Sword and Gold, and the Canadians in Juno, were luckier.

Omaha was the main concern for Eisenhower, worried of the dangers that presented to the 1st Division, the Big Red One, and the 29th, who had to storm it. The Germans had plagued the waters with mines and obstacles to prevent landings at high tide. Following up, a strip of sand stretched 200 meters, rising gently against a sea wall that offered some cover against the machine-gun nests. A marshy grassland buffered between the sea wall and the steep bluffs, where the bunkers awaited. There were few accesses to the heights, and those were heavily fortified with strongpoints manned by the 352nd German Division, formed mainly by Osttruppen (captured Poles and Hiwis).

Omaha seen from the bluffs. Taken during my trip to Normandy

Omaha is a vast beach. At low tide the sands spread over 300 m. Omaha today. It hasn’t changed much, except for the sea wall, which was flattened by American engineers after its capture. Author: Anton Bielousov. Source

On the left flank, massive cliffs known as Pointe du Hoc, housed a German battery on top, overlooking Omaha. A battalion of Rangers had the undesirable mission to climb it up with rocket-fired grappling irons, and take it. The first wave, confident the astonishing pounding of the ships had would ease their beach-walk, would be dismayed to discover most of the defences were intact. The air raids and the naval bombardment in Omaha had been pretty much useless. Even the salvos of explosive rockets failed to reach the sands, and sunk in the waters.

Fortunately for the Americans, half of the 352nd had been sent to investigate exploding dummies dropped south of Carentan. Five-foot waves wildly slapped the landing crafts, with the Americans down with sea-sickness, spilling vomit in their shields and then tossing it overboard as if bailing water, leaving them exhausted for the dreadful task ahead. Mines, submarine obstacles, and German artillery complicated the landing even more, but it was too late to retreat.

#5 The bloody Omaha beach

On the 6th of June 1944, approximately at 6:30am, the ramparts descended. Immediately the crafts were sprayed with streams of MG-42 bullets piercing flesh and metal alike. To avoid the welcome party, the over cumbered soldiers jumped over the sides, many drowning in the process because of their wounds and excessive weight equipment. Mines and artillery blew the survivors to pieces, who rushed to take cover behind the anti-tank obstacles dotting the beach.

Blood rising up and down with the tide welcomed the following vessels, struggling to find the way ashore amidst a wreckage of blown up crafts, geysers made by the artillery, and floating corpses. On the sands the wounded cried in despair with their guts out, begging for their mothers, and the para-medics could do little for them but soothing their inevitable deaths with a double dose of morphine.

Paralysed by fear, many G.I. (US soldier) would not answer, they would simply cuddle in fetal position and sob. Most rifles and sub-machines guns didn’t work, they had retrieved the condoms sealing the muzzles too early. But the planners of Neptune had staked high on the waterproofed DD Sherman Tanks, which were essentially floating tanks landing to provide support.

The rough sea swallowed many DD before reaching Omaha. In panic, they had been dropped too far from the coast. Once in position, the surviving Shermans begun pounding hell upon the bunkers, and providing a much needed steel shield to the infantry.

It took the bravest leaders to begin to mobilise the paralysed squads, and sheltering them under the sea wall. ‘If you stay on the beach you’ll die!’. Spurred by Colonel Charles Canham of the 116th Infantry regiment, and the Brigadier General Norman D. Cota of the Big Red One, improvised battlegroups blew up several points in the barbed-wire entanglement protecting the sea wall, with their torpedoes Bengalore. Slowly but steady, successive waves of infantry successfully took those improvised ‘exits’, and a vicious fight for the bunkers begun. Flamethrowers, grenades and burst of sub-machine gun filled the concrete emplacements.

The minefields slowed down the advance, but engineers worked hard to clear the path for further infantry and supplies to arrive. By noon, over 19.000 men had landed on Omaha, and even attacked Colleville-sur-Mer, leading to one of Omaha’s exit corridors. The beach that lay behind the men of the 1st and the 29th, had become a cemetery for over 2.000 of their comrades.

#6 The landings in Caen area

The US 4th division attacking Utah had a far easier time, and only suffered 200 casualties, whereas the British and Canadian troops pushed even further inland, aiming for Caen and the Carpiquet airfield. The Brits of Montgomery’s 21st British Army Group, paused for a Tea break (according to their American and Canadian colleagues), losing the momentum, and wasting a unique chance when Caen laid exposed. They would dearly paid the mistake with thousands of lives, before Caen was finally liberated on mid-July.

#7 Were the D-Day landings successful?

By the end of the 6th of June, the Allies had failed to take any key objectives. But solid footholds had been secured, and a steady supply of reinforcements allowed them to gradually expand and link the sectors in the coming weeks. Their overwhelming naval and air superiority (only two German planes had flown over the beaches on the D-Day), scattered Rundstedt’s large Panzer formations heading to repel the invaders, just as Rommel had predicted. The Blitzkrieg, the concentration of Panzer divisions that Germany had so successfully applied on early years, was no longer possible.

The Wehrmacht was now resigned to secure the front, thus preventing the British Army of marching straight to Paris. But the cost had been high. More than 4.000 Allied soldiers had lost their lives in the landings, with a total of 10.000 casualties. Over 3.000 French civilians lost their lives in the Allied air-raids. Many hundreds of thousands were to lose their lives in the following months, during the liberation of Normandy.

But what if the Western Allies had failed in their invasion attempt? Maybe the Red Army would have reached France before them? Surely the war would have costed more millions of lives and suffering, and a total different post-war and Cold War scenario in Europe would have emerged, with a more empowered USSR.

Today there are 27 War cemeteries in Normandy, containing the bodies of over 100.00 men. Germans, Americans, French, Poles, Canadians, etc. The young men that captured the beaches, and the young men that defended them, forever resting under a sea of white crosses.