The battle of Stalingrad, August 1942 to February 1943, was the biggest and bloodiest battle ever fought. It’s regarded as the turning point of the Second World War, which saw Nazi Germany and the Axis powers defeated by the Allies, led by Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and the United States of America. In Stalingrad more than two million men fought on both sides, and casualties amounted to more than a million. But, was Stalingrad the most decisive battle of WW2? Did the Nazis have a real chance to defeat the colossal Red Army of the Soviet Union, and win the war? Let’s find out.

#1 Operation Barbarossa

June 22nd 1941. Germany invaded the USSR (Soviet Union), violating their common pact of neutrality, the 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. More than four million soldiers belonging to Germany and its Axis allies (Romania, Hungary and Italy) were divided in three groups of armies: North, Centre, and South.

Proof of Hitler and the Germans counting on a short war, is that some of their protagonists failed miserably to hit the mark with their forecasts. Captain Von Rosenbach-Lepinski said: “In four weeks we’ll be home”.

The initial advance of the Wehrmacht (German Armed Forces) was swift and captured millions of Soviet soldiers during the summer months, but the Soviet Union was vast, and the German offensive was stalled by the onset of the Russian winter, and repelled just within 30 km from Moscow, their main objective.

#2 The road to Stalingrad

Their offensive resumed in spring 1942, this time down-south in the Caucasus, where the Group of Armies South had taken most of the Ukraine in 1941. Their advance threatened to capture the Baku oilfields, the main source of oil for the USSR.

In June 1942, Hitler decided to split the Army Group South into Army Group A and B. Group A was to seize the Caucasus and secure the Baku oilfields, which would have virtually immobilised the Red Army. Meanwhile, the Group B, formed by the Sixth German Army and elements of the Fourth Panzer Army, were to protect Group A’s flank, by taking the area outside the city of Stalingrad (modern day Volgograd).

The German troops were excellently coordinated, and despite their Panzers (tanks) being inferior to the versatile Soviet T-34, concentrated Panzer columns, combined with superior manoeuvrability, quickly turned the hordes of T-34s into scrap piling up on the extensive Ukrainian steppe. In addition to, the leadership of the Red Army had been critically purged before and during the war. Stalin and his trust issues.

For the Soviet soldier the choice was… Well, there was no choice really. Surrendering was considered a treason to the Motherland and the families of the surrendered suffered ostracism and deprivation from the state. Stalin’s famous order of 1942 ‘Not a step back’, had lines of machine guns manned by the NKVD (secret police), shooting at their own fleeing comrades.

#3 The civilians of Stalingrad

Convinced of the immediate collapse of the Soviet Armies in the Caucasus, Hitler ordered the fateful decision of taking the city of Stalingrad. Capture of Stalingrad meant splitting Russia in two, and Stalin urged Chuikov, commander of the 62nd Army defending the city, to protect it or die in the attempt. Civilians were forbidden to evacuate to the safe side of the Volga. More than 44.000 would die in the ensuing battle.

On Sunday 23th August, the Luftwaffe (German Air Force), flying the Russian sky unopposed, began to pulverize Stalingrad. The commander of the Fourth Air Fleet, Wolfram Freiherr von Richtofen (cousin of the famous First World War Ace, the ‘Red Baron’), failed to realize that the debris created by the 1000 tons of bombs, was creating the perfect environment of urban warfare, suited for ambushes.

At their pleasure, the German aircraft began to shoot the hundreds of boats in the Volga, evacuating the wounded, and bringing fresh supplies and recruits to die in Stalingrad. Needless to say, the NKVD shoot any deserters who jumped in the water, panicking because of the screaming sirens of the German Stukas machine-gunning them.

#4 The Snipers of Stalingrad

On 13th September, vanguard units of the Sixth German Army, under Friedrich Paulus command, reached Stalingrad’s outskirts. The defending 62nd and 64th Army had but 40.000 men left and few tanks, however, they made the most of the debris, improvising it into barricades, and grooming a soldier the Germans feared most than anything else: the sniper.

Under legendary shooters like Vasily Zaytsev, ‘sniperism’ became a doctrine, and thousands rushed to learn from him. Sixth Army officers and soldiers learnt to crawl, and fear constantly for their lives, just as the Red Army had had reasons enough to fear snipers like Simo Häyhä, during the 1939 Winter War.

The most strategic point of the city was the Mamayev Kurgan, a hill whose emplacement allowed German artillery to batter the boats in the Volga and the Soviet positions at ease. The crudest battles took place there, constantly disputing the ownership of the hill. For many years after the battle, fragments of bone and bullets could still be found on the slopes.

#5 No land beyond the Volga

Chuikov was in dire straits. Germans at his threshold, and Stalin showing his teeth on his garden, but fortunately for him and his men, the 13th Guards Division commanded by Rodimtsev, crossed the Volga in time to save the day. Their motto became: ‘There was no land beyond the Volga’, and their intervention crucially stalled the German offensive.

The Landser (German soldier) hated Stalingrad’s urban fighting. Their characteristic Blitzkrieg was useless there. Heavy resistance took place in every house, with flamethrowers, grenades and ambushes as the main domestic appliances. Danger came from everywhere, with Zaytsev and the snipers adding a further strain, if not a bullet, in the German head. The Landser contemptuously called the battle of Stalingrad, Rattenkrieg (War of the rats), in permanent fear of the camouflaged Russians, awaiting from behind the rubble or the basements, to shoot at his back while passing by.

German soldiers manning a machine gun. Stalingrad. September, 1942. Copyright: Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-617-2571-04/CC-BY-SA 3.0. Source

Soviet squad fighting amidst the rubble of the buildings. Copyright: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-R74190 / CC-BY-SA 3.0. Source

Soviet soldiers in the ruins of the Red October Factory. Author: Gerogij Zelma. Source

In words of Antony Beevor, one of the most reputed historians of WW2, most of Stalingrad’s fighting consisted in small skirmishes. Squads of six or eight men armed with knives, sub-machines guns and grenades, sprouting from anywhere, especially during the nights, and attacking by surprise.

Another nightmare for the Landser was the Katyusha, a truck that fired dozens of rockets. It was named after the popular, Russian war song, Katyusha, and its frightful whistle made the Germans’ blood curdle. It was a terribly effective method of psychological warfare.

Russian soldiers weren’t off the mark at all, when they said: “We the Russians were better prepared for Stalingrad. We had no illusions above the cost, and we were willing to pay it”.

However, gradually the Sixth Army gained the upper hand and had almost reached the Volga banks, the last redoubt of the 62nd and 64th armies. Both sides were exhausted and short of ammunition. The battle wasn’t over yet, and with November, winter arrived in Stalingrad.

#6 The fall of Stalingrad?

11th November. The Sixth Army begun their final assault. Zhukov, the deputy commander-in-chief of the Red Army, second only to Stalin, had knew all along Stalingrad couldn’t resist forever. Two months ago, on 12th September, Zhukov and Vasilevsky, Chief of Staff, had presented a plan to Stalin.

Unbeknownst to the Germans, fresh Soviet armies had been trained, supplied, and deployed with utmost secrecy towards the flanks of the Sixth Army. Those flanks were protected by Romanian, Hungarian and Italian divisions, whose main deficiency was the lack of tanks and anti-tank weapons.

Over a million men and almost a thousand tanks were allocated for Zhukov’s planned offensive. Preparations were kept under extreme secret and orders passed by word of mouth. In addition to, troops only travelled under the cloak of the night.

#7 The turning point of Stalingrad

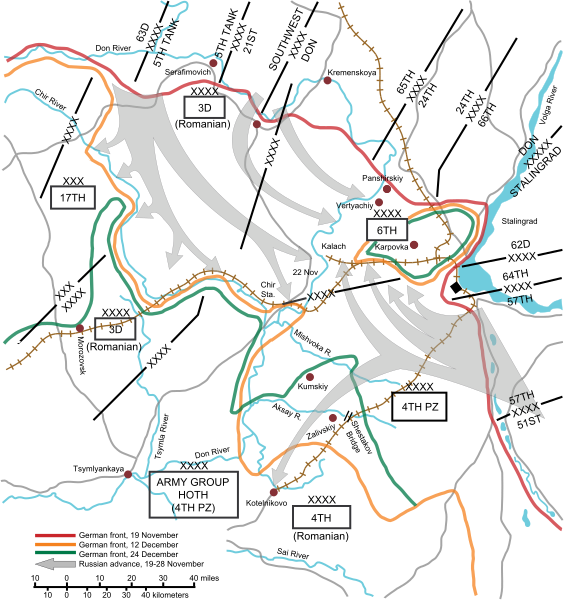

Thursday 19th 1942. Zhukov and Vailevsky’s Operation Uranus was at last unleashed. Their goal was the destruction of the enemy flanks and the encirclement of the Sixth Army within Stalingrad using two main throngs.

Without anti-tank weapons, and only light tanks to face the fearsome T-34, Romanian and Italian resistance soon collapsed. The Soviet throngs, north and south of Stalingrad, advanced quickly towards their meeting point in Kalach River, driving through behind the German lines, while the Sixth Army, unaware, kept fighting in Stalingrad.

Paulus dismissed all warnings, claiming both the sectors under attack were out of his area of responsibility. Paulus, a general lacking initiative and scared to death of Hitler, decided to wait for orders from the Führer headquarters. According to Anthony Beevor, had Paulus withdrawn the tanks engaged in Stalingrad, and launch those against the throngs behind the Sixth Army, the encirclement might had been repelled.

With his decision of, literally doing nothing, Paulus sealed the fate of the Sixth Army, and perhaps of the whole war. We all should be thanking Paulus right now.

#8 The Kessel and the rats

For the Soviet soldiers spearheading Operation Uranus, it was the most joyous day of the war, for it was time to exact revenge on those who desecrated the motherland. On 22nd November, the encirclement was completed. The Sixth Army and parts of the Fourth Panzer Army were trapped between the Volga and the Don rivers. A total of more than 290.000 Axis soldiers, including captured Russians who fought with them (called Hiwis).

During the first months of war, when the Germans trapped Soviet Armies, they called those pockets of encircled enemies, Kessel (cauldron). Now they were the ones being cooked in a Kessel, short of supplies, ammunition and with an increase of dysentery and lice. Hitler was assured by Göring, commander-in-chief of the Luftwaffe, that the Sixth Army would be fully air-supplied, but needless to say, supplies delivered were ridiculously short. Hitler was furious over Göring, but nevertheless vowed to never renounce Stalingrad, and urged Paulus to resist until help would come.

With the Army Group A in retreat from the Caucasus, in order to avoid their own encirclement, the Sixth Army begun to realize they had been left on their own. Some choose to believe in Hitler’s promises of rescue, but others acknowledged they were a necessary sacrifice, in order to save Erich von Manstein’s Army Group A. Meanwhile, the Red Army regained the Caucasus with Operation Little Saturn, and blocked the rescue attempt of the Forth Panzer Army, thus destroying the last hope for the 6th Army.

#9 The end of the bloodiest battle ever

On the 10th of January the Red Army was ready for Operation Koltso (Ring). The seven Soviet armies pinning the Sixth Army in Stalingrad begun to crush the Kessel. German resistance was fanatical, and despite starvation, diseases, frostbites and gangrene, despite the awareness of the futility of resisting, the Landser turned down any idea of surrender. The Soviet armies suffered 26.000 casualties during the first days, but their sheer advantage in men and material, had already decided the outcome of the battle. The Sixth Army was virtually out of food, oil and ammunition.

On the 31st of January, units of Shumilov’s 64th Army reached Paulus’ Headquarters, and discussed terms of surrender with Paulus second. Despite allowing commanders to surrender independently, Paulus constantly refused to give the general order. An isolated northern pocket of the Kessel, under the authority of general Strecker, withstood the increasing Soviet pressure for another two days.

#10 Aftermath

The battle of Stalingrad officially ended on 2nd February, 1943. Of the 91.000 German prisoners captured in the Kessel, barely 5.000 would see home again, even many years after the end of the war. The Red Army had suffered 1.1 million casualties, almost half of them fatal. The industrial city on the Volga, once home of 850.000 souls, was a burnt skeleton with 10.000 starved civilians.

The Battle of Stalingrad turned the tide of the war against Nazi Germany. The bloodiest battle in world’s history was over. It would take two more years for the Red Army and its allies, to fulfil the promise the surviving Soviet soldiers made to the German prisoners, in the ruins of Stalingrad: “That’s how Berlin is going to look!”

Did the Nazis have a chance to win the battle? Have they had the capacity to defeat the sturdy Red Army, and perhaps (unfortunately) win the war? Once the Sixth Army was trapped during Operation Uranus, the battle was decided. But Paulus had a unique chance to break the encirclement, using their own Panzers engaged in the city. And even more critical, was Hitler’s obsession to capture, the strategically speaking, unnecessary Stalingrad. Avoiding Stalingrad would had proved more decisive than any victory.

More than two thousand years before the battle of Stalingrad, Sun Tzu, author of The Art of War, said: It is best to win without fighting. Thanks God, Hitler seemingly never read him.

Brilliant post. So much information crammed into limited spacing. Fantastic use of maps and photographs too!

LikeLike

Thanks, I think it can be confusing enough without maps, they make such a crucial difference

LikeLike