“I am the one who gave you more kingdoms than you had towns before”

These words were uttered by Hernán Cortés to none other than the King of Spain and Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, after the latter failed to recognise him. A brazen and boastful claim but not a hollow one, as Cortés was the most successful and famous of the Spanish Conquistadores. At the head of a small but proficient force, plus hundreds of thousands of native allies he recruited to his cause, he brought down the Aztec Empire, then at its zenith as the most powerful nation in the New World. His feat changed the history of the continent forever, paving the way for Spanish dominance and colonisation of most of the American continent for well over 200 years. But how did he succeed against all odds? Keep reading to find out.

1# From Spain to Cuba

Hernán Cortés was born in 1485 in Medellín, then Kingdom of Castille (modern Spain), a member of the lesser nobility. Like so many of his peers at the time, he sought to improve his lot in the recently discovered American continent, then called West Indies by Europeans. He quickly proved his mettle by taking part of the conquests of Hispaniola and Cuba, the first Spanish domains in the New World. He befriended the first governor of Cuba, Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, whose authorisation he secured to dispatch an expedition to explore and colonise the lands north of Cuba. Cortés’ was to become the third, and the only successful one, of the exploration missions sent to the lands we know as Mexico today.

In 1519, Cortés departed La Havana, at the head of a flotilla of ten ships, 500 soldiers, plus hundreds of native Cuban porters, and a handful of women to cook for his men. His expedition almost floundered before starting, for he had fallen out with Velázquez, but ignoring the orders to hand over his command, he departed Cuba. This wouldn’t be the first, nor the last time that Cortés would clash against the legal, appointed, authorities, nor the last when he’d stake his freedom, his life, and that of his men, on the success of his endeavour.

2# Meeting La Malinche

Cortés made landfall on Cozumel, on the Yucatán Peninsula, where he had then stroke of luck to find Geronimo de Aguilar, a Spaniard who had shipwrecked there years ago, and who, forced to live with the local Mayans, could speak Chontal Maya. With his new translator at his side, he travelled north to Tabasco, where the hostile locals had a first taste of the devastating European style of warfare. Even though their forces outnumbered the Spaniards 20.000 to 500, they had never seen horses or guns before, and Cortés only lost two men in their subjugation. More important, on questioning them about gold, the Tabascans pointed north and said a word: Mexico.

It didn’t take Cortés long to find these Mexicans, these people who called themselves Aztecs, and who inhabited the Valley of Mexico. During this first fortuitous meeting, Cortés discovered an even greater asset in the person of Malintzin, later called La Malinche, a slave gifted to him by the subjugated Tabascans as tribute, and who besides being fluent in Chontal Maya, had also mastered the Aztec language, Nahuatl. She would become her chief interpreter and lover. When, through her, the Aztecs enquired Cortés as to the reason of his presence there, he didn’t hesitate to confess:

“I and my companions suffer from a disease of the heart which can be cured only with gold.”

3# The Valley of Mexico and the Aztec Empire

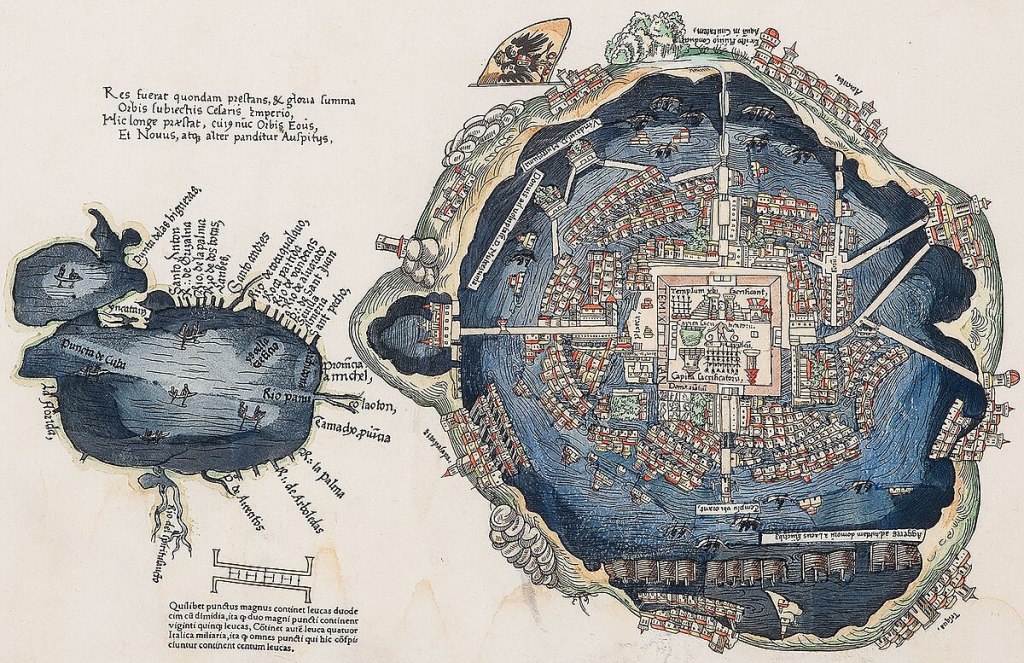

The fact that they had blatantly tried to bribe him away, had only ironically managed the opposite, inflaming the Spaniards’ greed. As the generous Aztecs gifts demonstrated, the Aztecs had gold in abundance, and what better place to find more that in Tenochtitlan? The fabled Aztec capital, from where the emperor Moctezuma over 6 million subjects and tributaries. With this new destination in mind, Cortés took his fleet to the eastern coast of central Mexico, where he founded the first Spanish settlement in the mainland, Villa Rica de la Vera Cruz, today’s Veracruz. By this act, he wasn’t simply establishing a base of operations, he was also claiming patronage and protection from the king, without whose he’d have remained as an outlaw who had mutinied against Velázquez.

The Aztec empire was in essence, an alliance of three state-cities, Tenochtitlan, Tezcoco, and Tlacopan, of which the former had asserted its dominance over the other two, as well as exercising indirect rule over many neighbouring towns and confederacies, including the Cempoalans and Totonacs. These resented Tenochtitlan’s increasing demands for tribute, but specially human victims for their daily sacrifices —a fundamental aspect of Aztec religion—. Amongst the most prominent Aztec opponents, were the Tlaxcallans, whom initially antagonised (and attacked) the Spaniards, but quickly finding out the truth of the old adage: the enemy of my enemy is my friend. The Spaniards’ wondrous weapons, but specially their hounds and horses—the latter entirely unknown in the Americas until the arrival of the Europeans—contributed to make them look like akin to gods to the native population, and who were powerless to oppose Cortés’ dictates to topple their idols and convert to Christianism.

Always the skilled diplomat, he recruited allies while reassuring the Aztec envoys that he was a friend of Moctezuma, and requested to meet him personally. Before he begun the long trek to Tenochtitlan, he dispatched a ship to Spain with all the treasure he had so far collected, also seizing the opportunity to send away those with questionable loyalties to Velázquez. Those who stayed, Cortés wanted fully committed, and to ensure they would remain so, he took the fateful decision to scuttle all his ships, leaving them stranded. The only way left, was forward, to fabulous riches and ever-lasting glory. It was to win or die.

4# Tenochtitlan and Moctezuma

With his Tlaxcallan and Totonac allies, Cortés’ first significant stop was in Cholula, halfway between Veracruz and Tenochtitlan, and subject to the Aztecs. The city was famous for its pyramid, the largest structure in America then, and housing a great temple dedicated to Quetzalcoatl, one of the main Aztec deities. But Cortés wasn’t going to overlook the fact that daily human sacrifices were practiced within its walls. However, it’s unlikely that religious differences brought about the destruction of Cholula. Many other confederations in the Valley of Mexico often recurred to human sacrifice, including Cortés’ native allies. The official version still stands that from the lips of La Malinche, he learnt of an Aztec-induced Cholulan plot to kill him and his men, and he pre-emptively struck, unleashing a wild killing that was settled with the lives of more than 5.000 locals.

He hurried to reassure Moctezuma’s envoys that he didn’t blame their master for the Cholulan duplicity, and insisted to meet him in person. Faced with the implicit threat that Tenochitlan might suffer the same fate as Cholula, Moctezuma had no choice but to agree. Cortés wasn’t initially interested in destroying Tenochtitlan, at least not if one takes at face value his first impression of “The City of Dreams”, as he described it. A marvel of architecture unlike anything Europeans were accostumed to, the city was erected on the west half of the shallow, brackish, Lake Texcoco. Three causeways anchored it to the mainland, with moveable bridges that allowed canoes to move across, and canals that crisscrossed the city. It is estimated that Tenochtitlan had more than 200.000 inhabitants, making it one of the largest cities in the world at the time.

It was November 8th, 1519, when Cortés first entered the city and was graciously housed in the Palace of Axayacatl, erstwhile residence of Moctezuma’s father. This proved a blessing for Cortés, for he and his soldiers were housed in the heart of Aztec power, and very close to Montezuma himself. Cortés met him, receiving even more lavish gifts, and regaled him and his entourage with a show of military force, by making his men adopt several formations while discharging their harquebuses and light cannons. Providentially, Cortés learnt that his lieutenant in Villa Rica and six of his men garrisoned there, had been killed by Aztecs while supporting their Totonac allies. Cortés saw an opportunity, and using the attack as a pretext, he demanded that Moctezuma move into Axayacatl, where he’d be kept under his vigilance. Daunted by the military prowess, seemingly magical, of the bearded, steel-clad, foreigners, Moctezuma agreed on the condition that the pretence of his free will was maintained in public.

5# Trapped in Tenochtitlan

With this bloodless coup, Cortés had become de facto, shadow ruler of the Aztec Empire. His first measure was, logically, to demand punishment for those involved in the deaths at Villa Rica, and had Moctezuma watch his countrymen burnt at the stake, with his ankles chained like a common criminal. The proud emperor of the Aztecs, nearly a living god to the common people, had been humiliated, his spirit broken. But as he became more and more pliant to Cortés’ demands, his people became more and more agitated. Sensing their dangerous mood, the Spanish Captain-General took precautionary steps by making Moctezuma and the principal Aztec leaders swear an oath to King Charles V, and by having his captains gather all the treasure they could.

Then more worrying news from Villa Cruz arrived. Velázquez had sent his friend and lieutenant, Pánfilo de Narváez, at the head of eighteen warships, to subdue and arrest Cortés. Leaving a small force under captain Pedro de Alvarado to keep his puppet ruler in check, Cortés marched to confront Narváez, whom he quickly defeated despite being outnumbered. His small but battle-tested force proved superior in all aspects to Narváez’s untested men. Nearly all of them defected to his side under his alluring promises of vast amounts of Aztec gold. Narváez himself lost an eye during the confrontation, and spent the following two years as Cortés’ prisoner.

His rearguard secured, Cortés hurried back to Tenochtitlan, where things had spiralled out of control in his absence. Having gotten wind of an insurrection against him, Alvarado had foolishly decided to struck first, and during the Festival of Toxocatl, he and his men massacred thousands of Aztec nobles and warriors. As a result, they became besieged inside Axayacatl Palace, and only the timely arrival of Cortés in June 24th 1520, saved them from certain starvation. Cortés reprimanded his rash subordinate, and on Moctezuma’s suggestion, sent the latter’s brother, Cuitláhuac, to find food. Unknowingly, he had released a plague, for the vengeful survivors of the Aztec leadership deposed Moctezuma and crowned Cuitláhuac as the new emperor.

6# La Noche Triste

Cuitláhuac wasted no time less in resuming the siege of Axayacatl. Fierce street fighting went on for a week, and despite the superiority of their weapons, the Spaniards proved incapable of breaking off the siege. The Aztecs could easily replenish their substantial loses and rest, but the Spaniards didn’t have that luxury. Their horses, which had proved so devastating on the open field, were useless in the narrow city streets, with their slippery cobblestones and high rooftops, from where the Aztecs pelted them at leisure. It was one of these projectiles that ended Cortés’ attempts at diplomacy, when Moctezuma was struck down as he attempted to calm down the attackers at Cortés’ insistence. He later died of his wounds on June 30th.

His greatest asset lost, Cortés made the decision to abandon the city, and on the midnight of July 1st, he and his army fled Axayacatl under the cover of night. Of the three city causeways, only the Tacuba one (on the north) remained intact, and although it initially appeared that they’d get out unnoticed, the Spaniards were spotted. They were forced to fight a retreat battle across the entire, narrow causeway. Nearly 600 of them, almost all of them Narváez’s, and thousands of Tlaxcallans perished. Most drowned, dragged to the bottom of Lake Texcoco by the weight of their weapons, and the treasure they had stuffed their pockets with. Perhaps a kinder fate than the survivors, whose beating hearts were torn from the chests, and offered to Huitzilopochtli, the chief war deity of the Aztecs. Such event was christened by the survivors as “La Noche triste” The Sad Night.

7# A narrow escape

The only hope of salvation for Cortés and his ragged band of survivors, lay in reaching the lands of the Tlaxcallans. Constantly harassed and delayed by Aztec skirmishes, they soon found their path barred by a hostile army led by Matlatzincatzin, another of Moctezuma’s brothers. Outnumbered then to one, exhausted, hungry, and wounded, another man would have meekly accepted his certain end. But not Cortés. The Battle of Otumba proved one of his finest moments, in which despite counting with little more than ten serviceable horses, he deftly unleashed them again and again against the Aztec formations, ploughing gaps which the infantry could exploit.

The victory could be well described as miraculous, as well as costly. Cortés himself nearly perished, two of his fingers crushed, his skull fractured, and he lost consciousness as they crawled to Tlaxcallan safety, only to regain it several days later. Human loses between La Noche Triste and the battle were many, almost all horses were lame or dead, all gunpowder was gone, and all the treasure, the main factor that ultimately kept the men loyal, lay at the bottom of Lake Texcoco.

8# The epidemic of Smallpox

Although Tenochtitlan lay out of reach, Cortés realised his position wasn’t as untenable as it appeared. The Tlaxcallans were, if anything, more determined to destroy the Aztecs, and two of their most prominent leaders, Xicotenga the Elder and Maxixcatzin, taking advantage of Cortés’ vulnerable position, renegotiated their alliance to their advantage. Cortés had no choice but to agree to everything, without Tlaxcallan support his enterprise was doomed. Tenochtitlan was far away and well-protected, but not so its allies, like the province of Tepeaca, south of Tlaxcalla, and after routing its army, Cortés founded a new town there, Segura de la Frontera.

His luck had turned once more. On the subsequent months, as he destroyed or subjugated other Aztec tributaries, he received further reinforcements. Several ships landed at Villa Rica, bringing men, gunpowder, and invaluable horses, bringing his force of Spaniards up to 1.300, plus tens of thousands of Indian allies. Although the most effective of his allies was one against which the Aztecs had no possible defense: smallpox. Thought to have arrived to the New World in one of the Narváez ships, by late December 1520 it had wiped out as much as half the population in many towns and cities, the emperor, Cuitláhuac, amongst them. Smallpox was a completely new disease in the Americas, against which the natives had no defences, while most of the Spaniards, having been exposed to it as children, were immune.

With the Aztecs busy burying their death, Cortés made significant gains when he received a pledge from Tetzcoco, one of the three city-states that ruled the Aztec Empire. Not only it put him on the threshold of Tenochtitlan, but it also allowed him to realise his plan to launch a small fleet of brigantines to Lake Texcoco. Built in Villa Rica by the skilled carpenter, Martín López, they were dismantled, carried over to Tetzcoco, and reassembled into a canal dug for that purpose between the city and the lake’s shore. With these, Cortés was confident that he could bring the Aztec capital, and its new emperor, Cuauhtémoc, to his knees. While this took place, Cortés and his captains secured the northern and southern shores of the lake, tightening the ring around the increasingly isolated Tenochtitlan.

9# The Fall of Tenochtitlan

It was May 26th 1521. Cortés had at his disposal 86 horsemen, 118 harquebusiers and crossbowmen, and 700 infantrymen armed with the renowned Toledo steel. He also had three heavy guns, plus fifteen light field pieces, and his thirteen brigantines. His native allies now amounted to 200.000, far more than the Aztecs could field. His plan consisted in dividing his land forces in three, with Alvarado and Olid ordered to secure the causeways of Tacuba (Tlacopan) and Coyoacan, while Sandoval would take the one at Iztapalapa. The northernmost causeway, Tepeyacac, Cortés opted to leave open in the optimistic belief that the beleaguered Aztecs would use it to flee.

But that thought was far from Cuauhtémoc’s mind. His men repeatedly broke the causeways that the Tlaxcallans hurried to repair, barricades were erected to bar the Spaniard’s advance, and the bottom of the lake was filled with sharp stakes to breach the hulls of the big brigantines. Instead of a swift, decisive victory, the Spaniards and their allies were faced with a prolonged and tiresome, hit-and-run operation that dragged on for a month.

Fearing above all, a repetition of the events of La Noche Triste, in which his army became bottle-necked in one of the causeways, Cortés resisted his men’s entreaties to order an all-out assault to decisively knock out the enemy. But against his better judgement, he finally relented, ordering a massive, concerted assault on June 30th. The Aztecs were expecting them, as he had feared, and ambushed the Spaniards as they thought themselves safe at the causeway’s end. Sixy-five to seventy of them were captured (Cortés himself was nearly apprehended) and their comrades, having safely retreated to the other end of the causeway, were still close enough to hear their screams, as the Aztecs sacrificed them that very same night.

News of his reverse caused some of his allies to defect back to Cuauhtémoc’s camp, but in the open fields the Spaniards still proved invincible thanks to their horses, and Sandoval effortlessly crushed the rebel armies, simultaneously and successfully quashing any future rebellious tendences amongst them. After the last causeway was finally sealed off, the situation within Tenochtitlan became desperate. Starvation set in, and the Spaniards made it even worse when they destroyed the aqueducts that brought fresh water to the city, for that of Lake Texcoco was brackish, and therefore undrinkable.

Even then Cuauhtémoc refused all of Cortés’ entreaties to surrender. Even as most of his capital was slowly taken in a vicious hand-to-hand combat that made the Fall of Tenochtitlan one of the costliest battles in history, with as many as 200.000 Aztecs and 30.000 Tlaxcallans perishing. The last Aztec stronghold destroyed, the marketplace of Tlatelolco, in the northern edge of the city, Cortés begun the mop-up of the last pockets of resistance. He had hoped to spare the city which had mesmerised him on his first visit, but the obstinate Aztecs, fighting every house and street, made him decide otherwise. On August 13, 1521, two months and a half after the battle for the causeways had begun, Cortés ordered the destruction of the last remainder of Aztec resistance on the fringes of the city, while his brigantines hunted down or captured those who tried to flee in canoes, Cuauhtémoc amongst them.

10# Aftermath

With the fall of Tenochtitlan, the Aztec Empire ceased to exist. Those of its denizens who hadn’t perished at the hands of the Spaniards, from hunger, or victims of the smallpox, were put in chains and sold into slavery. Cuauhtémoc himself was treated with dignity due to his rank, at the beginning at least, but when he failed to produce the treasure than the Spaniards had hoped to find inside the city, he was tortured and later killed. Most of the treasure had been indeed sunk during La Noche Triste, but the new land was still wealthy enough to make it a significant gain to the Spanish Crown.

For these deeds, King Charles V showered Cortés with honours and the titles of governor, captain-general, and chief justice of this New Spain. Many other towns were founded there by its first governor, including Mexico City, on the smoking ruins of Tenochtitlan. In a matter of years, Aztec culture and particularly its religion, were completely replaced by that of the Spaniards. Cortés’ expeditions to conquer Honduras and Guatemala proved a failure, and his last years were marred by the mysterious death of his wife, Catalina (in which many believed him responsible), and by his litigation with the king. He believed that he had been unjustly rewarded, due to the king’s refusal to appoint him as viceroy, the highest office in the newly conquered American colonies.

He produced a son with La Malinche, one of the first, if not the very first, mestizo who combined both Mexican and European ascent. For virtue of their parentage, it’d not be wholly unreasonable to regard them as the father and mother of modern Mexico, mixing the blood of Aztec and Spaniard. Such view has and will always remain contentious, since the foundations of modern Mexico entailed the death, enslavement, and displacement of millions of people as a direct result of Cortés’ actions. His legacy, as that of any conqueror must be, will be forever loathed by those whom he conquered, but praised by those on whose behalf he conquered. But however polemical his legacy remains, his skill as a general, diplomat, and inspired leader of men, is unquestionable. His conquest of Mexico was, and remains, the largest addition of land and treasure to the Spanish Empire achieved by one man.