On July 4th 1776, in the midst of the American Revolutionary War, the Second Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence, proclaiming the 13 American colonies as independent from Great Britain. In 1783, the latter acknowledge it in the Treaty of Paris. Like its European counterpart, the French Revolution, the American Revolution is often evocative of ideals of liberty, sovereignty, and justice. The latter is often regarded as a precursor to the former, and although both drew on the principles of the enlightment and sought to install representative democracies that guaranteed the rights of man, both did so out of very different motivations. And both had distinctive and lasting outcomes. What then, where these causes of the American Revolution and how it came to be? Read all about it and more below:

1# The Colonies

The arrival of Christopher Columbus to the American continent in 1492 marked the beginning of a period of conquest and colonization by the Europeans. Although England’s first successful colony in this new, bountiful, land was only established in 1607 in Virginia, in 1732, with the creation of Georgia, Great Britain boasted of thirteen thriving colonies. And a population of less than 2.000 in the early 17th century, had swollen to nearly 2.5 million on the late second half of the 18th century.

Who were those colonists? English? British? Always a destination for immigrants seeking opportunities, the New World also appealed to to the poor and discontent, seeking to start with a clean slate. Religious dissidents from England or Scotland, impoverished Irish immigrants, or Africans brought as slaves. Germans, Welsh, Swedes, and Dutch too. Each brought their distinctive background, language, religion, and values. And the only common link bounding them in this melting pot, was loyalty to the monarch of Great Britain and trade with the mother island. And her enemies too.

2# The Seven Years’ War

Between 1756 and 1763 Great Britain and France clashed over their respective colonies in North America. Great Britain emerged victorious and doubled its possessions at the expense of its archenemy, but the national debt skyrocketed as a result of the war effort. Moreover, worried about future French attempts to recover lost ground, Great Britain sought to keep a permanent 10.000 strong army in American soil.

Parliament believed the colonies ought to foot the bill, for the war had been fought and the army raised to protect them. Following this logic, the Sugar Act of 1764 was passed to help raise some new revenues. A Molasses Act had existed since 1733 to that effect, but it wasn’t tightly enforced, and the new act sought to rectify that.

The colonists disagreed. The new act came at a time of economic depression as a result of the Seven Years’ War, and even though the new act actually lowered the existing, non-enforced tax, the colonists were outraged because they believed that parliament, a body in which they had no representation, didn’t have the right to tax them. In time, this would evolve into the famous motto: no representation, no taxation.

3# The Townshend Acts

Active resistance came only with the passing of the Stamp Act a year later. The act required printed material to be produced in stamped paper brought from London, which included a revenue stamp. The protests over the legitimacy of Parliament to raise taxes on the colonials was brought to the fore again, and this time the colonials used force to make the stamp tax collectors resign their posts, and prevented the landing of the infamous stamped paper. All colonial assemblies supported the protests and claimed the act was a violation of their fundamental rights. Although Parliament ultimately backed down and repelled it in 1766, the seeds of disagreement and conflict were sowned.

The following year saw a new wave of acts, the Townshend Acts, enacted by Westminster, further inflaming the colonists’ mood against Parliament. The Revenue Act raised new taxes on glass, lead, paint, paper and tea (all to be imported from England); the Comissioners of Customs enforced tight shipping regulations, the New York Restraining Act, which curtailed its local assembly until they complied with quartering British soldiers stationed there. The Indemnity Act, to refloat the collapsing East India Company, and last, the Vice Admiralty Court Act, which transferred local courts’ jurisdiction over violations of customs and smuggling to the admiralty courts.

4# The Boston Massacre

The Townshend Acts tirggered further unrest and disobedience in the colonies. Non-importation and boycott to English products, although slow, finally took root. Letters from a farmer in Pennsylvania, by John Dickinson, reinforced the popular belief that Parliament had the right to relgulate trade but not to tax the colonies; and the Massachussets Circular Letter, by Samuel Adams and James Otis, and passed by the Massachussets House of Representatives, concurred with Dickinson and first hinted at the possibility that the colonial legislatures should harmonise or perhaps unite in some manner.

It was at this time that the suspicion that England, represented by Parliament, sought to destroy their liberties, was confirmed in the colonists’ eyes. And that Catholicism, thinly veiled under Anglicanism, sought to enslave them. Having fled political or religious persecution in their homeland, it was little surprising that they thought so, even if there was little basis to support those claims.

In 1768, riots broke out in Boston over the seizure of the ship Liberty, owned by John Hancock, by British authorities accusing the former of smuggling. Although the procedures against Hancock were quietly dropped, troops had been deployed in Boston to enforce the Townshend Acts and quell unrest, which had the unintended effect to escalate the tensions. Again, in Boston, a private quarrel between a British soldier and a wigmaker’s apprentice quickly attracted a mob, which begun taunting the soldiers, pelting them with snowballs and other objects, until they got the best of the redcoats. They opened fire against orders from their commanding officer, Preston, killing five and wounding many others. Preston, and his men were trialled and absolved, a fact which didn’t contribute to quell popular anger.

5# The Sons of Liberty and The Boston Tea Party

The new cabinet of Lord North finally decided to rescind the unpopular Townshend Acts, all save one. The Indemnity Act remained, only to be superseded by the 1773 Tea Act. Its aim was two-fold: to cut off tea smuggling (at the time smuggled Dutch tea reigned supreme in America), and to force colonials to purchase East India Company tea and pay its duties, making them indirectly comply and thus agree, to Parliament’s claims of their supreme right of taxation.

Although the act actually lowered the existing (and again non-enforced) duties on tea, the colonials bristled at Parliament’s scheme and prevented the new tea to be unloaded. Only in Boston, did Governor Hutchinson, resolved to enforce the act at all costs. On December 16th 1773, the Sons of Liberty (an organization defending the colonist’ interests), with Samuel Adams at its head, boarded the ships waiting to unload the new tea, and dumped it into the waters of the harbour. 90.000 pounds worth 10.000£ (well over a million in modern currency) went to the fish. More important that the economic cost was the fact that the act triggered a new wave of acts, this time aiming to punish colonial disobedience.

6# The Intolerable Acts

In Britain, these are known as coercive acts, and as the name suggests, were designed to punish the perpetrators of the Boston Tea Party. The Boston Port Act of 1774, closed the port of Boston until the cost of the damaged tea had been paid by the colony of Massachussets. The Massachussets Government Act followed suit, bringing the colony under direct rule of British administration by giving extraordinary powers to the Governor. The Administration of Justice Act, which provided for royal officials to be judged in Great Britain, instead of within the colony where they had allegedly perpretated the crime.

Finally, the New Quartering Act, which allowed for British soldiers to be quartered in occupied buildings if no suitable quarters were found by the colonial authorities. And although not considered part of the Coercive Acts by Britain, the colonists considered the Quebec Act as such. The latter enshrined Catholic rights in the British Province of Quebec, a fact which ruffled the feathers of the strongly protestant, neighbouring, colonists. It also granted Quebec rights of settlement in the Ohio Country, a prerogative which the thirteen colonies had claimed as their own ever since the end of the Seven Years’ War.

7# The First Continental Congress

It was the restrictions imposed on Massachussets and Boston that had the greater impact. The other colonial legislatures feared the imposition of direct British rule such as that in Massachussets, and on September 1774 they responded by sending their representatives to a First Continental Congress of the thirteen colonies. Which for all its grand title, lacked in representation from the rest of the American continent.

For the first time, king George III was associated with the wrongdoings of the crooked Parliament, and it was decided that all trade with Britain cease until the Intolerable Acts were repealed. A policy known as nonimportation, nonconsumption, and nonexportation. Moreover, before it was officially dissolved in October 26th, Congress also officially petitioned the king for a redress of their grievances.

8# Lexington and Concord

Resolved to protect their rights at all costs, militias were raised and organised under the approval of Congress. Again, Boston took to the spotlight. The Sons of Liberty stockpiled arms in anticipation of a confrontation with Thomas Gage, the military governor sent by London. Parliament concurred with Gage’s opinion that Massachussets was in a state of rebellion, so was the king, who dismissed the letter of grievances presented to him by the First Continental Congress. King and Parliament ordered Gage to arrest the Sons of Liberty and confiscate their weapons, and Gage decided that the best way to accomplish thus, was by seizing the colonials’ arms and ammuniton stored in Concord and Worcester.

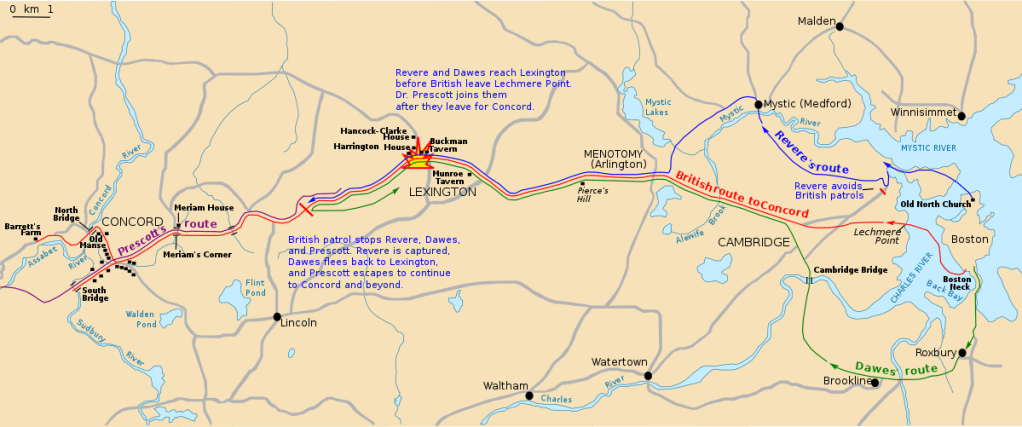

On April 18th 1775, he dispatched over 700 hundred regulars, the British redcoats, towards Concord. The Sons of Liberty and Patriots, Samuel Prescott, William Dawes, and Paul Revere, rode ahead and alerted the militias to muster in order to stop them. Militamen and British regulars clashed in a minor skirmish in Lexington. The regulars brushed the defenders aside and continued their march to Concord. There the battle was fiercer, and although the redcoats managed to destroy some ammunition and supplies, they were driven off with hundreds of casualties by an outnumbering militia force.

9# The Declaration of Independence

The Battles of Lexington and Concord are officially regarded as the start of the Revolutionary War. A Second Continental Congress was conveyed in Philadelphia in May 10th 1775, which confirmed the necessity to take arms against British regulars. George Washington was named as commander-in-chief of a colonial army to be raised, formed of regulars as well as militia. In those early stages there was no talk of independence yet, indeed the idea was far from most delegates’ minds, or the average colonial for that matter. Most still clung to the hope of reconciliation, which is why Congress petitioned the king to mediate once more. But George III had already declared the colonies in rebellion, following news of the Battle of Bunker Hill.

It was only in 1776, following a shift of public sentiment in favour of independence― thanks in part to Paine’s Common Sense―that Congress felt confident enough to move towards it. Moreover, as Virgina’s delegate, Richard Henry Lee, explained, only an independent state could secure the economic and military support of Britain’s European foes, particularly France. At his instigation, Congress passed the “Resolution for Independence”, (also “The Lee Resolution”), declaring the colonies as independent states. On July 4th Congress passed the Declaration of Independence, composed by Thomas Jefferson, with the aid of John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman and Robert Livingston.

Its drafting has served since to inspire many other declarations of independence around the globe, and each 4th of July, the modern United States commemorate and celebrate the deed as Independence Day. The country’s first constitution, “The Articles of Confederation” agreeing on a union and a weak, central government for the new 13 states was approved a year later. The United States Constitution superseded it in 1789, thus completing the American Revolution. The surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown in October 19th 1781, against a combined American-French force under Washington and Rochambeau, shook Great Britain’s confidence in a victorious outcome. A fact confirmed in 1783 when they finally acknowledged the independence of the nascent United States of America.